One In A Million

2 posters

Page 1 of 1

One In A Million

One In A Million

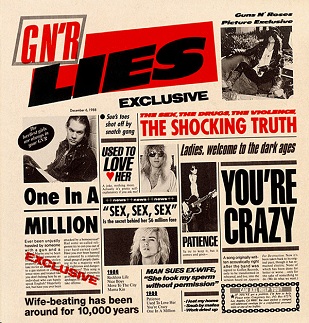

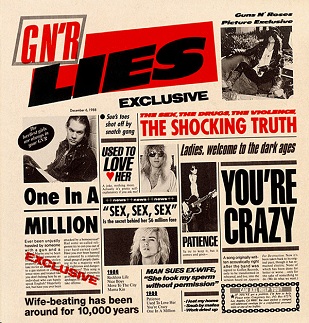

Album:

GN'R Lies, 1988, track no. 7.

Written by:

Axl Rose.

Musicians:

Vocals: Axl Rose; lead guitar: Slash; rhythm guitar: Izzy Stradlin and Duff McKagan; bass: Duff McKagan; drums: Steven Adler.

Live performances:

This song was played for the first time October 30, 1987, at an acoustic gig at the CBGB's, USA. It was later played at the Limelight, USA, on January 31, 1988, and in Mears in July 30, 1988. In total it has, as of {UPDATEDATE}, at least been played {ONEINAMILLIONSONGS} times.

GN'R Lies, 1988, track no. 7.

Written by:

Axl Rose.

Musicians:

Vocals: Axl Rose; lead guitar: Slash; rhythm guitar: Izzy Stradlin and Duff McKagan; bass: Duff McKagan; drums: Steven Adler.

Live performances:

This song was played for the first time October 30, 1987, at an acoustic gig at the CBGB's, USA. It was later played at the Limelight, USA, on January 31, 1988, and in Mears in July 30, 1988. In total it has, as of {UPDATEDATE}, at least been played {ONEINAMILLIONSONGS} times.

Lyrics:

Guess I needed

Sometime to get away

I needed some peace of mind

Some peace of mind that'll stay

So I thumbed it

Down to sixth and L.A.

Maybe your greyhound

Could be my way

Police and niggers

That's right

Get out of my way

Don't need to buy none of your

Goldchains today

I don't need no bracelets

Clamped in front of my back

Just need my ticket till then

Won't you cut me some slack

You're one in a million

Yeah, that's what you are

You're one in a million, babe

You are a shooting star

Maybe someday we see you

Before you make us cry

You know we tried to reach you

But you were much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Immigrants and faggots

They make no sense to me

They come to your country

And think they do as they please

Like start a mini Iran

Or spread some fucking disease

They talk so many goddamn ways

It's all Greek to me

Well some say I'm lazy

And other say that's just me

Some say I'm crazy

I guess I'll always be

But it been such a long time

Since I knew right from wrong

It's all the means to an end, I,

I keep on movin' along

You're one in a million

Yeah, that's what you are

You're one in a million, babe

You are a shooting star

Maybe someday we see you

Before you make us cry

You know we tried to reach you

But you were much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Radicals and racists

Don't point your finger at me

I'm a small town white boy

Just tryin' to make ends meet

Don't need your religion

Don't watch that much TV

Just makin' my livin', baby,

Well that's enough for me

You're one in a million

Yeah, that's what you are

You're one in a million, babe

You are a shooting star

Maybe someday we see you

Before you make us cry

You know we tried to reach you

But you were much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Guess I needed

Sometime to get away

I needed some peace of mind

Some peace of mind that'll stay

So I thumbed it

Down to sixth and L.A.

Maybe your greyhound

Could be my way

Police and niggers

That's right

Get out of my way

Don't need to buy none of your

Goldchains today

I don't need no bracelets

Clamped in front of my back

Just need my ticket till then

Won't you cut me some slack

You're one in a million

Yeah, that's what you are

You're one in a million, babe

You are a shooting star

Maybe someday we see you

Before you make us cry

You know we tried to reach you

But you were much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Immigrants and faggots

They make no sense to me

They come to your country

And think they do as they please

Like start a mini Iran

Or spread some fucking disease

They talk so many goddamn ways

It's all Greek to me

Well some say I'm lazy

And other say that's just me

Some say I'm crazy

I guess I'll always be

But it been such a long time

Since I knew right from wrong

It's all the means to an end, I,

I keep on movin' along

You're one in a million

Yeah, that's what you are

You're one in a million, babe

You are a shooting star

Maybe someday we see you

Before you make us cry

You know we tried to reach you

But you were much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Radicals and racists

Don't point your finger at me

I'm a small town white boy

Just tryin' to make ends meet

Don't need your religion

Don't watch that much TV

Just makin' my livin', baby,

Well that's enough for me

You're one in a million

Yeah, that's what you are

You're one in a million, babe

You are a shooting star

Maybe someday we see you

Before you make us cry

You know we tried to reach you

But you were much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Much too high

Quotes regarding the song and its making:

Writing the song:

Describing the song as social realism:

Axl would defend the song with arguing that if black people use that word, why couldn't he?

He would also argue that the song was meant as humour and that he used the the terms exclusively for some people:

Much later, Doug Goldstein would support this explanation:

Axl would also have to defend accusation of attacking gays:

Axl would also say that people can't be trusted with the song, and offer an apology:

Before the fierce media reaction to the song took place, the band played it live at least three times (October 30, 1987, at an acoustic gig at the CBGB's, USA; at the Limelight, USA, on January 31, 1988; and in Mears in July 30, 1988). Despite this, in early 1990, Duff would claim they had never played the song live:

The band members, who had recorded the song and played it live, reacted in various ways to the backlash.

Duff consistently defended the decision to include the song:

As criticism mounted, the other band members would some times distance themselves from the song, and blame it on Axl and his stubbornness, or defend Axl and point to artistic freedom of speech. Regardless of whether they defended the song or not, they would consistently put all the blame on Axl and trivialize their own responsibility as band members and musicians on the recording.

In the August edition of RIP Magazine, 1989, Slash penned a letter as a response to a fan letter that had been published in the May issue:

As the band started touring the 'Use Your Illusion' records in 1991, there were rumors that the Ku Klux Klan would show up at the shows and claim that the band supported racism:

Axl would discuss KKK and David Duke while playing two shows in Dayton on January 13 and 14, 1992:

Later, Axl would discuss trying to engage the audience in the KKK rumours:

Axl would revisit this theme on January 27 in San Diego:

Axl would also talk about David Duke in interviews, like in an interview he did in September 1992:

I hit L.A. with a backpack, a piece of steel in one hand and a can of maize in the other. And guys were trying to sell me joints everywhere, and some black guy turned me on to the bus station. So, I found the bus station. And there'll be a song about the bus station on our EP called "One In A Million".

One of the most shining moments was when [Axl] sat with an acoustic guitar on the edge of his sofa in his trashed apartment and sang 'One in a Million' [from their recently-released Ep, GNR Lies]...and just floored me. It's an amazing song, but it's not very often I hear something that raw or in an early stage where you go, 'That's the whole sentiment. That's the whole execution and that's the whole song.' Usually you hear things and you say, 'Well, this has got a lot of potential and we ought to do this.'

Axl had an apartment at the time, and he said: “Come on over. I want to run a song by you.” He sat on his bed with an acoustic guitar and played me One In A Million. At that moment he seemed incredibly vulnerable. It was almost like his personality shape-shifted and transported back to the very moment he experienced the things he was talking about in that song. The hook of the song was rather plaintive. ‘One in a million’ – a faint wish in his mind that he might ever be.

Describing the song as social realism:

We were aware of what kind of flak we were going to get, which is why I put an apology right on the cover of the record. Living on the streets you go through a lot of hard times and a lot of my hard times were with people of different races or different beliefs. I haven't anything against those people. I'm not a racist. The songs are just (an account) of what happened to us. If you change the words or soften them, you change the truth.

I started writing about wanting to get out of LA , getting away for a little while. I'd been down to the downtown-L.A. Greyhound bus station. If you haven't been there, you can't say shit to me about what goes on and about my point of view. There are a large number of black men selling stolen jewelry, crack, heroin and pot, and most of the drugs are bogus. Rip-off artists selling parking spaces to parking lots that there's no charge for. Trying to misguide every kid that gets off the bus and doesn't quite know where he's at or where to go, trying to take the person for whatever they've got. That's how I hit town. The thing with 'One in a Million' is, basically, we're all one in a million, we're all here on this earth. We're one fish in a sea. Let's quit fucking with each other, fucking with me.

'One in a million' is about...... I went back and forth from Indiana eight times my first year in Hollywood. I wrote it about being dropped off at the bus station and everything that was going on. I'd never been in a city this big and was fortunate enough to have this black dude help me find my way. He guided me to the RTD station and showed me what bus to take, because I couldn't get a straight answer out of anybody. He wasn't after my money or anything. It was more like, "Here's a new kid in town, and he looks like he might get into trouble down here. Lemme help him get on his way." People kept coming up trying to sell me joints and stuff. In downtown L.A the joints are usually bogus, or they'll sell you drugs that can kill you. It's a really ugly scene. The song's not about him, but you could kinda say he was one in a million. When I sat down after walking in circles for three hours, the cops told me to get off the streets. The cops down there have seen so much slime that they figure if you have long hair, you're probably slime also. The black guys trying to sell you jewelry and drugs is where the line 'Police and niggers, get out of my way' comes from. I've seen these huge black dudes pull Bowie knives on people for their boom boxes and shit. It's ugly […] I don't have anything against someone coming here from another country and trying to better themselves. What I don't dig is some 7-11 worker acting as though you don't belong here, or acting like they don't understand you while they're trying to rip you off. [Axl mimics an Iranian] "Wot? I no understand you". I'm saying "I gave you a 20, and I want my $15 change!" I threatened to blow up their gas station, and then they gave me my change. I don't need that.

When I use the word immigrants, what I'm talking about is going to a 7-11 or Village pantries - a lot of people from countries like Iran, Pakistan, China, Japan et cetera, get jobs in these convenience stores and gas stations. Then they treat you as if you don't belong here. I've been chased out of a store with Slash by a six-foot-tall Iranian with a butcher knife because he didn't like the way we were dressed. Scared me to death. All I could see in my mind was a picture of my arm on the ground, blood going everywhere. When I get scared, I get mad. I grabbed the top of one of these big orange garbage cans and went back at him with this shield, going, "Come on!" I didn't want to back down from this guy. Anyway that's why I wrote about immigrants. Maybe I should have been more specific and said, "Joe Schmoladoo at the 7-11 and faggots make no sense to me." That's ridiculous! I summed it up simply and said, "Immigrants."

I'll get lambasted and filleted all over the place over that song. Dave Marsh will be writing about this 'We Are The World' consciousness, but Dave, I don't know where you were doing your 'We Are The World' consciousness, but we were getting robbed at knifepoint at that time in our lives. 'One In A Million' brought out the fact that racism does exist so let's do something about it. Since that song, a lot of people may hate Guns N' Roses, but they think about their racism now. And they weren't thinking about that during 'We Are the World.' 'We Are the World' was like a Hallmark card.

However that song makes them feel, they think that must be what the song means. If they hate blacks, and they hear my lines and hate blacks even more, I'm sorry, but that's not how l meant it. Our songs affect people, and that scares a lot of people. l think that song, more than any other song in a long time, brought certain issues to the surface and brought up discussion as to how fucked things really are. But when read somewhere that l said something last night before we performed "One in a Million," it pisses me off. We don't perform "One in a Million".

Axl would defend the song with arguing that if black people use that word, why couldn't he?

I used words like police and niggers because you're not allowed to use the word nigger. Why can black people go up to each other and say, "Nigger," but when a white guy does it all of a sudden it's a big put-down. I don't like boundaries of any kind. I don't like being told what I can and what I can't say. I used the word nigger because it's a word to describe somebody that is basically a pain in your life, a problem. The word nigger doesn't necessarily mean black. Doesn't John Lennon have a song 'Woman Is the Nigger of the World'? There's a rap group, N.W.A., Niggers with Attitude. I mean, they're proud of that word. More power to them. Guns N' Roses ain't bad. . . . N.W.A. is baad! Mr. Bob Goldthwait said the only reason we put these lyrics on the record was because it would cause controversy and we'd sell a million albums. Fuck him! Why'd he put us in his skit? We don't just do something to get the controversy, the press.

He would also argue that the song was meant as humour and that he used the the terms exclusively for some people:

To appreciate the humour in our work you gotta be able to relate to a lot of different things. And not everybody does. Not everybody can. With ‘One in a million’, I used a word - it’s part of the English language whether it’s a good word or not. It’s a derogatory word, it’s a negative word. It’s not meant to sum up the entire black race, but it was directed towards black people in those situations. I was robbed, I was ripped-off, I had my life threatened! And it’s like, I described it in one word. And not only that, but I wanted to see the effect of a racial joke. I wanted to see what effect that would have on the world. Slash was into it.... I mean, the song says « Don’t wanna buy none of your gold chains today ». Now a black person on the Oprah Winfrey show who goes « Oh, they’re putting down black people! » is going to fuckin’ take one of these guys at the bus stop home and feed him and take care of him and let him babysit the kids? They ain’t gonna be near the guy ! I don’t think every black person is a nigger. I don’t care. I consider myself kinda green and from another planet or something, you know? I’ve never felt I fit into any group, so to speak. A black person has this 300 years of whatever on his shoulders. OK. But I ain’t got nothing to do with that. It bores me too. There’s such a thing as too sensitive. You can watch a movie about someone blowing all the crap outta all these people, but you could be the most anti-violent person in the world. But you get off on this movie, like, yeah! He deserved it, you know, the bad guy got shot... Something I’ve noticed that’s really weird about ‘One in a million’ is the whole song coming together took me by surprise. I wrote the song as a joke. West (Arkeen, co-lyricist of ‘It’s so easy’ amongst other songs) just got robbed by two black guys on Christmas night, a few years back. He went out to play on Hollywood boulevard and he’s standing there playing in front of the band and he gets robbed at knife point for 78 cents. A couple of days later we’re all sittin’ around watchin’ TV - there’s Duff and West and a couple other guys - and we’re all bummed out, hungover and this and that. And I’m sitting there with no money, no job, feelin’ guilty for being at West’s house all the time suckin’ up the oxygen, you know? And I picked up this guitar, and I can only play like the top two strings, and I ended up fuckin’ around with this little riff. It was the only thing I could play on the guitar at the time. And then I started ad-libbing some words to it as a joke. And we had just watched Sam Kinison or somethin’ on the video, you know, and I guess the humour was just sorta leanin’ that way anyway or somethin’. I don’t know. But we just started writing this thing, and when I sang « police and niggers, that’s right », that was to fuck with West’s head, cos he couldn’t believe I would write that! And it came out like that....then later on the chorus came about because I was like getting really far away, like ‘Rocket man’, Elton John. I was thinking about my friends and family in Indiana, and I realized those people have no concept of who I am anymore. Even the ones I was close to. Since then I’ve flown people out here, had’em hang out here, I’ve paid for everything. But there was no joy in it for them. I was smashin’ shit, going fuckin’ crazy. And yet, trying to work. And they were going, « Man, I don’t wanna be a rocker any more, not if you go through this ». But at the same time, I brought’em out, you know, and we just hung out for a couple of months - wrote songs together, had serious talks, it was almost like bein’ on acid cos we’d talk about the family and life and stuff, and we’d get really heavy and get to know each all over again. It’s hard to try and replace eight years of knowing each other every day, and then all of a sudden I’m in this new world. Back there I was a street kid with a skateboard and no money dreamin’ ‘bout being in a rock band, and now all of a sudden I’m here. And it’s weird for them to see their friends putting up Axl posters, you know? And it’s weird for me too. So anyway, all of a sudden I came up with this chorus « You’re one in a million », you know, and « we tried to reach you but you were much too high .... »(...) So that’s like, « we tried to reach you but you were much too high », I was picturing ‘em trying to call me if, like, I disappeared or died or something. And « you’re one in a million », someone said that to me real sarcastically, it wasn’t like an ego thing. But that’s the good thing, you use that « I’m one in a million » positively to make yourself get things done. But originally, it was kinda like someone went, « Yeah, you’re just fuckin’ one in a million, aren’t ya? », and it stuck with me. Then we go in the studio, and Duff plays the guitar much more aggressively than I did. Slash made it too tight and concise, and I wanted it a bit rawer. Then Izzy comes up with this electric guitar thing. I was pushing him to come up with a cool tone, and all of a sudden he’s comin’up with this aggressive thing. It just happened. So suddenly it didn’t work to sing the song in a low funny voice any more. We tried and it didn’t work, didn’t sound right, it didn’t fit. And the guitar parts were so cool, I had to sing it like.....HURRHHHH ! so that I sound like I’m totally into this.

The word was used [bleep] on the record, but that didn’t necessarily mean all black people. It just, you know – it meant, basically, lowlifes, people that were stealing to supply their drug habits...

Interview at Robert Williams’ exhibition, November 1988, from VH1 Documentary, 2004

It was originally written as comedy. It was written watching Sam Kinison during one of his first specials. I was sitting around with friends, drunk, with no money. One of my friends had just gotten robbed for seventy-eight cents on Christmas by two black men.

l played it on guitar and it was done very slow and in a different tone of voice and done very humorously. Well, that didn't work out when we recorded it because I had Duff play it on guitar -- because he could play it better and in better time -- and Izzy put this other guitar thing to it, and it evolved into something of its own. We didn't plan that song to be as forceful as it was. We walked into the studio, and boom, it just happened.

Much later, Doug Goldstein would support this explanation:

He was making a joke about how stupid people were in Indiana, where he grew up. He was showing the phobias of a 17 year old boy arriving in Los Angeles and being afraid of minorities because he didn't know them in his homeland. I keep telling him to explain it, but he says, ‘Did people ask Picasso to explain his work? I'm an artist.’ He says that if Lennon had written that song, people would understand.

Axl would also have to defend accusation of attacking gays:

Axl would also say that people can't be trusted with the song, and offer an apology:

[…] the racist thing is just bullshit. I used a word that was taboo. And I used that word because it was taboo. I was pissed off about some black people that were trying to rob me. I wanted to insult those particular black people. I didn't want to support racism. […] The racist thing, that's just stupid. I can understand how people would think that, but that's not how I meant it. I believe that there's always gonna be some form of racism -- as much as we'd like there to be peace -- because people are different. Black culture is different. I work with a black man every day (Earl Gabbidon, Rose's bodyguard), and he's one of my best friends. There are things he's into that are definitely a "black thing." But I can like them. There are things that are that way. I think there always will be. […] It's that way with people who are of the same race or same gender. Maybe now and then they'll reach a point where something happens, and they bond, and they're really close. But they're always going to have their differences. The most important thing about "One in a Million" is that it got people to think about racism. A lot of people thought I was talking about entire races or sectors of people. I wasn't. And there was an apology on the record. The apology is not even written that well, but it's not on the cover of every record. And no one has acknowledged it yet. No one.

I don't trust the audience with the song. I don't want to do "One in a Million" on stage and know that there's a lot of people out there in the crowd who are prejudiced and it's gonna help fuel their fire. It's enough to handle the fact that it's on a record and people use it for their own anthems for their own prejudiced-ness. I question myself every day. Should l pull it? Should I leave it? Do l leave it for the sake of artistic integrity? Do I pull it, do I censor myself? But wait, I'm against censorship. It's a really hard issue to constantly deal with. The only way to deal with it is to communicate about it. l don't like the damage that that song does, l don't like the prejudiced-ness, l don't like the way the song fuels people's prejudiced-ness, and that's a problem for me. l made an apology on the cover of the record. Looking at it now, it's not the best apology, but it was the best apology l could make back then. l knew people were going to be offended, and it says my apology is to those who take offense. Or to who may be offended, whatever it says. I was trying to explain the reasons why I was expressing myself in this way and apologizing if it did offend people. The apology is on the cover of every record. it's not a sticker; it's part of the cover. It's stuck in there with all kinds of other things on the cover -- it's done like a National Enquirer thing. l wrote it myself and put it on there, it was my Idea, and it's like it's been refused to be acknowledged. "One in a Million" has been used continually against Guns N' Roses and against myself, no matter what l had to say about it.

Yes, [the reaction to the lyrics] definitely helped me to be able to change. I went out and got all kinds of video tapes and read books on racism. Books by Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X. Reading them and studying, then after that l put on the tape and l realized, "Wow, I'm still proud of this song." That's strange. What does that mean? But l couldn't communicate as well as do now about it, so my frustration was just turned to anger. Then my anger would be used against me and my frustration would be used against me: "Look, he's throwing a tantrum."

My opinion is, the majority of the public can't be trusted with that song. It inspires thoughts and reactions that cause people to have to deal with their own feelings on racism, prejudice and sexuality.

l wrote a song that was very simple and vague. (...)l think I showed that quite well from where l was at. The song most definitely was a survival mechanism. It was a way for me to express my anger at how vulnerable l felt in certain situations that had gone down in my life. It's not a song l would write now. The song is very generic and generalized, and I apologized for that on the cover of the record. Going back and reading it, it wasn't the best apology but, at the time, it was the best apology I could make.

The song [=One in a Million] is very generic. it's very vague, it's very simple, it was meant to be that way, it was written that way. It was like, O.K., I'm writing this song as l want to -- l want this song to be like "Midnight Cowboy." That guy was very naive and involved in everything. The cowboy. My friend who got robbed, he was like Dustin Hoffman's character. l wanted the song to be written from that point of view. l wrote it to deal with my anger and my fear and my vulnerability in that situation, that l still felt uncomfortable with, that happened to me. That was the "police and niggers" line. But now we move on to another line that says, […] "Immigrants and faggots, they make no sense to me/ they come to our country and think they'll do as they please / like start some mini-Iran, or spread some fucking disease / and they talk so many goddamned ways / it's all Greek to me." […] The line about "faggots" was written after I heard a story from a sheriff about a man they had just arrested after just releasing from jail, and he had AIDS, and he was back out on Santa Monica Boulevard hooking. We were like, "Oh, my God." And this just happened to get stuck in the song, since we had a radical line like "police and niggers" -- we might as well go all the way now, we'll write something else just as obnoxious, because we were just writing off-color humor at the time. We were dealing with a situation that was really heavy, ugly, and scary, and so we were making light of it. l was being encouraged to write as l was writing. […] Then we move on to the gay issue. I hitchhiked a lot and I got hassled an awful lot. I was very naive, and very tired, and a guy picked me up and said l could crash at his hotel, and l woke up with the man trying to rape me. l almost killed this man, l was so frightened. l had a straight-edge razor and was freakin' out: Don't ever touch me again! Then the guy ran out the door. l was so scared and l felt so violated. l didn't know that l felt even more violated than l was in the situation because of what had gone on in my childhood and what l had pretty much buried-and didn't even remember.

I'm on a fence with that song. It's a very powerful song. l feel, as far as artistic freedom and my responsibility to those beliefs, that the song should exist. That's the only reason l haven't pulled it off the shelves. Freedom and creativity should never be stifled. Had l known that people were going to get hurt because of this song, then l would have been wrong. l was definitely wrong in thinking that the public could handle it.

Before the fierce media reaction to the song took place, the band played it live at least three times (October 30, 1987, at an acoustic gig at the CBGB's, USA; at the Limelight, USA, on January 31, 1988; and in Mears in July 30, 1988). Despite this, in early 1990, Duff would claim they had never played the song live:

We've never done it live, no.

Mick Wall, GUNS N' ROSES: The Most Dangerous Band in the World, Sidgwick & Jackson, U.K. 1991, 1993; interview from January 1990

The band members, who had recorded the song and played it live, reacted in various ways to the backlash.

Duff consistently defended the decision to include the song:

For a start, the “nigger” thing. Slash comes from a family that is half-black. My family is a quarter black... I mean, readers, listen to every lyric in the song! The song’s about Axl coming to LA for the first time on the fuckin’ bus. He was a fuckin’ green, wet-behind-the-ears white boy, and he was scared to fuckin’ death! That is what the song is about and that’s it, people can take it the way they want to. Of course, right now they’re gonna just fuckin’ slag us. I’d rather not get too much into it, though. If you can’t get anything out of it then don’t listen, is my message.

[…] I can understand some people taking offence to it, yeah. But, ultimately... why? All it is, is a tale about life actually in this fuckin’ town, downtown LA. OK, it’s a white guy telling the tale. So what? That's his story. All it is, is a white kid telling his tale. But I don’t want to say too much. Axl’s got such a reputation now that of course they’re gonna jump all over his ass - he said that dirty word, you know? I mean, check it out, I’ve been an uncle since I was two years old. My first nephew when I was two was black. It was my sister’s kid; she married a black guy. Now I have sixteen nephews and nieces and cousins and shit, lots of which are black, or part black.

I never heard the word "nigger" until I went to fuckin' school! Until I went to school I didn’t know there was a difference between black and white. Then at school you'd see them, the white kids giving a hard time to the black kids. Like, "Fuck you, nigger!" I was like, "Fuck you, you white fuckin' asshole!" Like, why are you calling him a nigger? What does it mean? I couldn't see the difference. So I've always felt very strongly about this. We were in Australia and there's this big skinhead movement down there. Slash and I wanted to come out and make a press statement or something while we were there, against the skinheads...[…] they were against the Aborigines, and they were against the blacks, and shit. They're so racist you wouldn't believe it. Slash and I are so against that shit. And so is Axl, so is Axl. He’s not prejudiced at all. There is no prejudice in this band. The simple thing about this song is that it is just a tale of what happens to a fucking kid from Indiana - not from London, or San Francisco, but from out of nowhere to the big city - and being scared off his ass. He didn't know the right words to use. So that is all it’s about, man.

[…] I can understand some people taking offence to it, yeah. But, ultimately... why? All it is, is a tale about life actually in this fuckin’ town, downtown LA. OK, it’s a white guy telling the tale. So what? That's his story. All it is, is a white kid telling his tale. But I don’t want to say too much. Axl’s got such a reputation now that of course they’re gonna jump all over his ass - he said that dirty word, you know? I mean, check it out, I’ve been an uncle since I was two years old. My first nephew when I was two was black. It was my sister’s kid; she married a black guy. Now I have sixteen nephews and nieces and cousins and shit, lots of which are black, or part black.

I never heard the word "nigger" until I went to fuckin' school! Until I went to school I didn’t know there was a difference between black and white. Then at school you'd see them, the white kids giving a hard time to the black kids. Like, "Fuck you, nigger!" I was like, "Fuck you, you white fuckin' asshole!" Like, why are you calling him a nigger? What does it mean? I couldn't see the difference. So I've always felt very strongly about this. We were in Australia and there's this big skinhead movement down there. Slash and I wanted to come out and make a press statement or something while we were there, against the skinheads...[…] they were against the Aborigines, and they were against the blacks, and shit. They're so racist you wouldn't believe it. Slash and I are so against that shit. And so is Axl, so is Axl. He’s not prejudiced at all. There is no prejudice in this band. The simple thing about this song is that it is just a tale of what happens to a fucking kid from Indiana - not from London, or San Francisco, but from out of nowhere to the big city - and being scared off his ass. He didn't know the right words to use. So that is all it’s about, man.

Mick Wall, GUNS N' ROSES: The Most Dangerous Band in the World, Sidgwick & Jackson, U.K. 1991, 1993; interview from January 1990

I think each individual has to interpret it as they like. As for me? I think it's kinda funny! It's real life, and this band has never minced words when it comes to real life. The song is basically Axl's view of coming to downtown L.A. for the first time. He was from Indiana, he was real green--and L.A. blew his mind. [...] You have to remember--we've lived all this stuff. When you saw these dirty white-trash (expletive) guys on Hollywood Boulevard--hey, that was us! [...] I'm sure it'll bother some people--and I can understand that. But the song is a way of describing what happened to us, not making any value judgments. [...] If you're just exposing aspects of life that are already out there, what's the problem with that? When I was 14, I thought Sid Vicious was cool, but I knew that didn't mean I had to OD on heroin. This is just our song--and we're not asking for everyone to like it. I don't think we have to be responsible for everybody else's opinion.

As criticism mounted, the other band members would some times distance themselves from the song, and blame it on Axl and his stubbornness, or defend Axl and point to artistic freedom of speech. Regardless of whether they defended the song or not, they would consistently put all the blame on Axl and trivialize their own responsibility as band members and musicians on the recording.

There's a line in that song where it says, “Police and niggers, get out of my way...” that I didn’t want Axl to sing, I didn’t want him to sing that but Axl’s the kind of person who will sing whatever it is he feels like singing. So I knew that it was gonna come out and it finally did come out. What that line was supposed to mean, though, was police and niggers, OK, but not necessarily talking about the black race. He wasn’t talking about black people so much, he was more or less talking about the sort of street thugs that you run into. Especially if you’re a naive mid-western kid coming into the city for the first time and there’s these guys trying to pawn this on you and push that on you...

It's a heavy, heavy, heavily intimidating thing for somebody like that. I’ve been living in Hollywood for so long I’m used to it, you know? But I didn’t want the song to be taken wrong, which always happens.

[…] in the context of the song those are the character’s true feelings - his mind is just blown away by what he sees. But there’s been a couple of instances where I've decided I was gonna do like an international press release to try and explain what some of this shit is about. Then I thought, no, fuck, that’s a waste of time...

But that kind of thing does bother me. Me, in particular. I mean, I’m part black. I don’t have anything against black individuals. One of the nice things about Guns N’ Roses is that we’ve always been a people’s band. We’ve never segregated the audience in our minds as white, black or green, you know? But with the release of "One in a Million” I think it did something that I don’t think was necessarily positive for the band, and it put us...

[…] whenever given the chance I try and say my piece about that, because it really isn’t... It doesn’t even have to be about blacks. The term ‘nigger’ goes for Chinese, Caucasians, Mexicans... blacks too, sure. But it’s just like a type of people that, you know, are street dealers and pushers. And that’s what it’s supposed to mean. It’s definitely something to attack us with. It’s a bona fide, real thing that they can actually say, you know, “Well, what about that?”

It's a heavy, heavy, heavily intimidating thing for somebody like that. I’ve been living in Hollywood for so long I’m used to it, you know? But I didn’t want the song to be taken wrong, which always happens.

[…] in the context of the song those are the character’s true feelings - his mind is just blown away by what he sees. But there’s been a couple of instances where I've decided I was gonna do like an international press release to try and explain what some of this shit is about. Then I thought, no, fuck, that’s a waste of time...

But that kind of thing does bother me. Me, in particular. I mean, I’m part black. I don’t have anything against black individuals. One of the nice things about Guns N’ Roses is that we’ve always been a people’s band. We’ve never segregated the audience in our minds as white, black or green, you know? But with the release of "One in a Million” I think it did something that I don’t think was necessarily positive for the band, and it put us...

[…] whenever given the chance I try and say my piece about that, because it really isn’t... It doesn’t even have to be about blacks. The term ‘nigger’ goes for Chinese, Caucasians, Mexicans... blacks too, sure. But it’s just like a type of people that, you know, are street dealers and pushers. And that’s what it’s supposed to mean. It’s definitely something to attack us with. It’s a bona fide, real thing that they can actually say, you know, “Well, what about that?”

Mick Wall, GUNS N' ROSES: The Most Dangerous Band in the World, Sidgwick & Jackson, U.K. 1991, 1993; interview from March 1989[/url]

[Being asked if it was okay on the grounds of artistic license]: Personally, no. I don’t think that that statement served any good. I think that should have been kept at bay altogether. But Axl has a strong feeling about it and he really wanted to say it. But then... God forbid that any of us should get arrested and end up in county jail. Can you imagine? "Yeah, that’s the guy who wrote that song!” You could be in some serious trouble with some of the guys in there. Much more trouble than just the cops.

Actually, that dawned on me a few days ago... We’re always in trouble with the police, that’s nothing new. And, you know, we’re not the only band to ever say something derogatory about the police. But there’s a point where you do things that make a statement, that are cool, and there’s another point where you do things that just aren’t necessary and you’re just asking for trouble. To ask for trouble and to intentionally put yourself in a position like that, to me, is not cool. As an artist you’re expected to make statements. But you’re supposed to make statements that make sense and come across clearly. You don’t want to make statements that are so, you know, so blatantly out of proportion, so blown out of proportion that it’s ridiculous, no subtlety in them at all.

My mom - who is black, right? - was in Europe and I talked to her on the phone a little while back, it was the first time we talked for ages. And I asked her if she’d heard the EP yet and she told me, no. But my little brother was out there, and when he came back he told me yeah, she had heard it. But she was so shocked that she didn’t know what to say to me on the phone. I thought about that and I thought, you know, I can understand that. So, ultimately, I can’t say... there’s nothing that I can say in the press that’s gonna cover it up.

Actually, that dawned on me a few days ago... We’re always in trouble with the police, that’s nothing new. And, you know, we’re not the only band to ever say something derogatory about the police. But there’s a point where you do things that make a statement, that are cool, and there’s another point where you do things that just aren’t necessary and you’re just asking for trouble. To ask for trouble and to intentionally put yourself in a position like that, to me, is not cool. As an artist you’re expected to make statements. But you’re supposed to make statements that make sense and come across clearly. You don’t want to make statements that are so, you know, so blatantly out of proportion, so blown out of proportion that it’s ridiculous, no subtlety in them at all.

My mom - who is black, right? - was in Europe and I talked to her on the phone a little while back, it was the first time we talked for ages. And I asked her if she’d heard the EP yet and she told me, no. But my little brother was out there, and when he came back he told me yeah, she had heard it. But she was so shocked that she didn’t know what to say to me on the phone. I thought about that and I thought, you know, I can understand that. So, ultimately, I can’t say... there’s nothing that I can say in the press that’s gonna cover it up.

Mick Wall, GUNS N' ROSES: The Most Dangerous Band in the World, Sidgwick & Jackson, U.K. 1991, 1993; interview from March 1989[/url]

I have a big problem with that lyric. I've talked to Axl many times about his lyrics. 'You don't need to say that, Axl. You're a fuckin' immigrant yourself. Everyone's a fuckin' immigrant in America. Don't you see you're putting down the whole of fuckin' America? And if they faggots, well so what?' Axl... is very... confused. But I was pissed off. I was very against that shit going on our record. 'Why'd you have to say that, Axl. It's hard enough just gettin' by.' [Pauses] But at the same time, y'know, this is just fuckin' rock 'n' roll music. When it's fucked up, it's more interesting. Whoever said this was responsible music, y'know? We're not fuckin' role models. At all. But 'One in a Million' is just flat-out racist. Like that about niggers trying to sell you gold chains.

That whole thing’s such a bunch of crap, man. Slash is half black. I come from a family that’s a quarter black. And if you [assumes a bullhorn voice] READERS OUT THERE, if you listen to all the lyrics, you might learn something. Axl was a fuckin’ wet behind the ears white boy in LA for the first time and he was scared to death! That’s what the song is about. People are just gonna have to take it whichever way they think is right. I mean, I don’t even like talking about it anymore. All it is, is a tale about a certain part of town. Yes, the story is told by a white kid, but that’s his story. And Axl’s got such a reputation now, he’s so well know, that of course they’re gonna jump all over his fucking ass. He said that dirty word. I mean, tell me about it. I’ve been an uncle since I was two. It was my older sister’s first child and it was a black kid. When I was growing up I was surrounded by nieces and nephews and cousins that were black, plus my own immediate family, who were white of course. Until I started school, I didn’t know there was a difference in black and white. That was the first time I heard anybody call somebody a nigger. I didn’t even know what the word meant. I still don’t. So I feel strongly about this. The bottom line is, Axl is not prejudiced. There is no prejudice in this band. It’s just a tale of what happened to a kid from Indiana, okay? And just being scared off his fucking ass by what he finds in the big city. [...] That song was that song. I can’t see us ever doing a song like that again. Not because we’re chicken shit to do it, just because that was then. There’s nothing left in our lives like that.

Kerrang, March 1990

When Axl first addressed the critics, his foremost priority was for him to say what he wanted to say and let the consequences fall by the wayside. That’s art. Sometimes you have to stand up for what you believe in. With “One...,” three quarters of the people who bitched misinterpreted what we were saying. I saw it coming […] No one is ever going to be satisfied! And you know, it’s amazing how people let other people run their lives. It's almost like there’s a robot or computer, and it’s setting you up to live the perfect, proper life. It’s just not right. Everybody's human, and no matter how morally correct you are as a human being, you're still going to make mistakes, because you're en-titled to your opinion. Opinions are personal. That’s why I hate critics. It's like, “We’re going to take this away from you, and we’re gonna ban this." Oh, yeah? Who says? Everybody’s complaining. Everybody’s writing letters. It's just one big, confused mess. But we somehow rise above, right?

Everybody on the black side of my family was like, 'What is your' problem? My old girlfriend said, 'You could have stopped it.' What am I supposed to say? Axl and I don't stop each other from doing things. Hopefully, if something is really bad, you stop it yourself. It was something he really wanted to put out to explain his story, which is what the song is about. Axl is a naive while boy from Indiana who came to Hollywood, was brought up in a totally Caucasian society, and it was his way of saying how scared he was and this and that. Maybe somewhere in there he does harbor some sort of [bigoted) feelings because of the way he was brought up. At the same time, it wasn't malicious. I can't sit here with a clear conscience and say, 'It's okay that it came out.' I don't condone it. But it happened, and now Axl is being condemned for it, and he takes it really personally. All can say, really, is that it's a lesson learned.

The stuff people are saying about our religious beliefs, our stance on homosexuality and all that, it was just one song and the song had nothing to do with making any kind of a statement. We didn't try to put people into any kind of categories or...I don't really know how to explain it. We weren't pointing fingers or anything like that. It was a song about one night, and it was something that Axl wanted to have there without trying to sound the way it sounded.

We all think maybe it was a mistake having it released because of the way people have reacted to it. When I listen to it in front of someone else, there's no other way to interpret it. We stuck our foot in our great mouth with that one.

We all think maybe it was a mistake having it released because of the way people have reacted to it. When I listen to it in front of someone else, there's no other way to interpret it. We stuck our foot in our great mouth with that one.

When Axl first came up with the song and really wanted to do it, I said I didn't think it was very cool... I don't regret doing 'One in a Million,' I just regret what we've been through because of it and the way people have perceived our personal feelings.

When Axl came up with it I was worried about recording the song. I wanted Axl to change the lyrics, because it would be seen by many as insulting. But hey, we did it, and I know Axl is talking about personal experiences and not being anti-black or anti-homosexual. So it should be looked at In this context. But we're being slammed for it. I do understand why some people object to those lyrics and I can't defend Axl for his language. But knowing where this came from, I appreciate he's not being racist or homophobic.

Living with that 'One In A Million' fall-out was heavy shit. I don't know if Axl learned anything from the experience - I would hope he did. Actually, Slash said the best things about that in some interview he did when he said that Axl's free expression was all well and good but he'd hate to think what would happen to any of the band if they got thrown in jail and had to explain the lyrics to the other guys doing time. 'Cos during that period I ended up in jail in Phoenix for a day. I found out. It was pretty fucked up.

It's only come up twice in the band's history where I had questions about whether a song's lyrics would be offensive. If it's like a little bit offensive and just makes the short hairs on the back of your neck stand up, that's all right. But there were only a couple that I thought might really be offensive. But, of course, we did them anyway. […] One of the songs was 'One in a Million.' But at this point, it's like so much water under the bridge, I don't want to get into it. We don't do it on purpose. We just write stuff that we feel like writing and it means something to us because it's all true to us. Therefore, I don't see any reason why we shouldn't be able to write it and then put it out. […] I don't see why there should be any rules or regulations on it. If you don't want to buy it, don't buy it. If it bothers you that much, don't listen to it.

And then as far as the whole racist thing is concerned, it had nothing to do with racism, or us speaking out against blacks or anything. I'm half black, so I was like: "Ok, this is a good one." I knew when Axl wrote the lyrics and I knew the story that went with it. I knew when he put it down on paper, it was gonna be recorded, it wasn't going to come across positive. So I took that one with a grain of salt. We got a lot of flack for that.

Everyone has a right to their opinion. I think the whole story with One In A Million was kind of exaggerated. I think some people took it more seriously than they should, maybe because they were looking for an excuse to dislike the band even more - maybe because they were jealous of us. They took it too far. It happens with many bands - people take their lyrics more seriously than they should. They take everything literally, but it’s just songs. Of course, if you think that there’s a hidden message and you go kill someone, that’s wrong. As far as lyrics go, I think they relate to the person who sings them - in our case, Axl. A solo guitar is Slash's thing, a piano solo is my thing. The words are Axl’s job, so we don’t interfere.

Pop & Rock, June 1993; translated from Greek

And then as far as the whole racist thing is concerned, it had nothing to do with racism, or us speaking out against blacks or anything. I'm half-black, so I was like: "Ok, this is a good one. And we're definitely not homophobic. Axl's view doesn't maybe match with what you're "supposed" to think. But the experiences Axl had of gays when he came to Los Angeles for the first time, you can't take that away from him.

In the August edition of RIP Magazine, 1989, Slash penned a letter as a response to a fan letter that had been published in the May issue:

To Tony W. of Fairfield, California, and whomever else it may concern:

I've never written to a publication before and never really expected to do so, but in this case I felt that it was well in order to make a sincere effort.

A letter printed in the Static section of the May issue of RIP caught my attention. The letter was written by Tony W. of Fairfield, California, and was more or less addressed to the rock and roll band Guns N' Roses. l am the lead guitarist and a cowriter for GNR, so it was fortunate that this particular issue came my way, especially since the bulk of GNR material that bypasses us is the usual carousing, chemical-abusing sexual highlights that comprise most of our publicity. This issue, though, contained a letter that shed some light on a more important subject. This was done by a legitimate fan of the band, rather than by an opinionated journalist with a quota to fill, thus deserving a response from someone in GNR without question!

All this aside, the purpose of Tony 's letter, I think, was to find out whether or not GNR is actually racist (referring to the content of one of our songs) or prejudiced. The song in question is off our EP, GNR Lies, and is called "One in a Million." The lyric that prompted Tony's curiosity as to our racial standing goes, "Police and niggers, get out of my way.” The term "niggers" being the case in question.

I think that down inside Tony knows the answer but it would satisfy a certain something to hear it from us. The answer is. NO! Not in any way is Guns N' Roses racist, prejudiced, bigoted or subject to any other title of racial discrimination. I cannot stress this strongly enough. I’m sorry that anyone would even start to think that about us in the first place, but I will add this much to emphasize and clarify.

The word nigger, by way of original definition (albeit slang), is a low-grade, lazy individual. An individual with no regard for anyone else. Low-class upbringing and moral standards. Human trash, if you like, but not a label for any particular ethnic group. A nigger could be a Caucasian. Asian, Italian, Latin or Black. It is from this definition GNR used the word nigger, not from the stereotypical one that is exclusive to blacks only. It’s a drag that some asshole somewhere, sometime, decided long ago that the word nigger and its meaning was deserved by the Black race Now it’s a household word used by racist morons the world over. And since it’s been this way for so long, it seems there's not much to be done about it. Being part black myself, I take offense to hearing the word nigger as well.

Anyway, I'll briefly summarize “One in a Million," and you can decide for yourself what we’re getting at. "One in a Million" is Axl’s autobiographical look back to when he picked up his bags and hitchhiked from smalltown Lafayette, Indiana, to downtown Los Angeles. The harsh contrast of L.A.'s fast pace, concrete, dog-eat-dog motif to Axl's middle-class, conservative background created the verses for "One in a Million," with “I'm one in a million," echoing the aspirations of kids everywhere to become somebody in the entertainment biz, being the chorus. The combination of verse and chorus should spell out the point of the song. Axl's reference to niggers was directed towards the characters one would encounter on the streets in downtown L.A., i.e. muggers, pimps, hookers, thieves, drug dealers, etc. . . . Not a common sight in Lafayette, for sure. But also very intimidating to a teenager coming from there and landing smack in the middle of LA. for the first time. Get the picture?

All the mentions of particular groups of people in this song are referring to the radical extremes (ex.: "immigrants and faggots." etc.). Hollywood is a radical extreme in itself. The words to "One in a Million” are not meant to insult. They are meant to verbalize the most decadent examples of everyday life in the big city.

In closing, I would like to add that the bottom line is, if anybody thought that we were bigots—DON'T. Nobody in this band is, nor is anyone in our whole organization. So if we offended anyone, it wasn't intentional.

Thanx for Listening,

SLASH

P.S. This isn't an excuse, just fact.

I've never written to a publication before and never really expected to do so, but in this case I felt that it was well in order to make a sincere effort.

A letter printed in the Static section of the May issue of RIP caught my attention. The letter was written by Tony W. of Fairfield, California, and was more or less addressed to the rock and roll band Guns N' Roses. l am the lead guitarist and a cowriter for GNR, so it was fortunate that this particular issue came my way, especially since the bulk of GNR material that bypasses us is the usual carousing, chemical-abusing sexual highlights that comprise most of our publicity. This issue, though, contained a letter that shed some light on a more important subject. This was done by a legitimate fan of the band, rather than by an opinionated journalist with a quota to fill, thus deserving a response from someone in GNR without question!

All this aside, the purpose of Tony 's letter, I think, was to find out whether or not GNR is actually racist (referring to the content of one of our songs) or prejudiced. The song in question is off our EP, GNR Lies, and is called "One in a Million." The lyric that prompted Tony's curiosity as to our racial standing goes, "Police and niggers, get out of my way.” The term "niggers" being the case in question.

I think that down inside Tony knows the answer but it would satisfy a certain something to hear it from us. The answer is. NO! Not in any way is Guns N' Roses racist, prejudiced, bigoted or subject to any other title of racial discrimination. I cannot stress this strongly enough. I’m sorry that anyone would even start to think that about us in the first place, but I will add this much to emphasize and clarify.

The word nigger, by way of original definition (albeit slang), is a low-grade, lazy individual. An individual with no regard for anyone else. Low-class upbringing and moral standards. Human trash, if you like, but not a label for any particular ethnic group. A nigger could be a Caucasian. Asian, Italian, Latin or Black. It is from this definition GNR used the word nigger, not from the stereotypical one that is exclusive to blacks only. It’s a drag that some asshole somewhere, sometime, decided long ago that the word nigger and its meaning was deserved by the Black race Now it’s a household word used by racist morons the world over. And since it’s been this way for so long, it seems there's not much to be done about it. Being part black myself, I take offense to hearing the word nigger as well.

Anyway, I'll briefly summarize “One in a Million," and you can decide for yourself what we’re getting at. "One in a Million" is Axl’s autobiographical look back to when he picked up his bags and hitchhiked from smalltown Lafayette, Indiana, to downtown Los Angeles. The harsh contrast of L.A.'s fast pace, concrete, dog-eat-dog motif to Axl's middle-class, conservative background created the verses for "One in a Million," with “I'm one in a million," echoing the aspirations of kids everywhere to become somebody in the entertainment biz, being the chorus. The combination of verse and chorus should spell out the point of the song. Axl's reference to niggers was directed towards the characters one would encounter on the streets in downtown L.A., i.e. muggers, pimps, hookers, thieves, drug dealers, etc. . . . Not a common sight in Lafayette, for sure. But also very intimidating to a teenager coming from there and landing smack in the middle of LA. for the first time. Get the picture?

All the mentions of particular groups of people in this song are referring to the radical extremes (ex.: "immigrants and faggots." etc.). Hollywood is a radical extreme in itself. The words to "One in a Million” are not meant to insult. They are meant to verbalize the most decadent examples of everyday life in the big city.

In closing, I would like to add that the bottom line is, if anybody thought that we were bigots—DON'T. Nobody in this band is, nor is anyone in our whole organization. So if we offended anyone, it wasn't intentional.

Thanx for Listening,

SLASH

P.S. This isn't an excuse, just fact.

As the band started touring the 'Use Your Illusion' records in 1991, there were rumors that the Ku Klux Klan would show up at the shows and claim that the band supported racism:

I mean, cuz we are the band that the Ku Klux Klan was supposed to be showing up at shows to pass up things. And it’s like, when a Ku Klux Klan guy is met, it’s like, “Out of here!” (points with his hand). […] Well, [the KKK] said they were going to and we were going to sue the Ku Klux Klan because they were trying to say we were supporting racism. And it’s like, they had a Grand Wizard and stuff. And it’s like, I fired off letters from the lawyers right away. I figure out, don’t even think about it, you know. You misinterpreted something I said. Don’t even think about it.

Axl would discuss KKK and David Duke while playing two shows in Dayton on January 13 and 14, 1992:

Now, I wanna ask your opinions about GN’R. I was reading in a magazine that we should have called these two new records “Our Hitler,” comparing me to Hitler; [that] I’m a troubled child and, basically, I’m Hitler, and if people listen they’ll all go to hell. What do you think of that? Being that we are the band that put out One in a Million, let me ask this question: how many redneck racist assholes do we have here tonight? And do you think that I’m a racist? Or a lot of you are just confused and you don’t know whether I am or not. I live in L.A., I’ve lived there for ten years. I’ve lived on the streets – I don’t anymore, but I used to. And, I mean, we hang out with people like Ice T and NWA. And it’s like, you can use whatever fucking language you want. I don’t need a bunch of jerkoff white fuckin’ people fuckin’ telling you I’m a racist cuz they don’t want our rock ‘n’ roll to exist. I had a meeting about a year-and-a-half ago with Arsenio Hall, cuz he was on TV calling me a racist and shit, and we went out and had a little talk. And he was like, 'The reason I’m having this talk is that I suddenly realized that the 70-80% of the white people in my organization were the ones telling me you’re a racist – not the black people that work with me.' It was the white people that didn’t want GN’R to be the fuck around.

But I read reviews on the albums and we got reviews describing us as – you know, that we should call the albums “Our Hitler” and, basically, we’re David Duke America’s house band. Fuck David Duke! And if you think that supporting something like David Duke is what we wrote a song like One in a Million about, then you can do yourself a favor, because you’re a real disillusioned motherfucker, and you outta just leave.

Later, Axl would discuss trying to engage the audience in the KKK rumours:

[Talking about trying to get a crowd reaction]: I approached it a bit differently when we did the first show in Dayton, Ohio. We'd been told we're the perfect house band for David Duke's America. And it's like, fuck David Duke, I don't like being associated with that. I asked the crowd: "Is that what you get out of this, that we're racists and you're supporting it? 'Cause if that's the case, I'm gonna go home. That's not why we're here." I asked the crowd about those things. I got some real interesting responses. The way they reacted was a little bit different than normal. There was silence in different places and cheering in others. You could tell that they were thinking for a minute.

Axl would revisit this theme on January 27 in San Diego:

You know, we just put out these records and I’ve read all kinds of reviews. I’ve been called everything. We should have called the record “Our Hitler;” that’s from a review I read. Yeah, I think Guns N’ Roses has a whole hell of a lot to do with Nazism and telling people what to do and killing [?], don’t you? They still don’t know what to make out of One in a Million. You know, it’s funny. The people mostly pissed off about what they call racism were the white people. There are a lot of white people that just don’t like rock ‘n’ roll in general, so, “Wait, now we’ve got a fucking target. They’re racist.” Is that what you people think we are and we mean? Is that all we are about? Because if it is, then we should probably go home. Because we get told that we should be – I think it was in Entertainment Weekly – “David Duke’s house band for America.” Fuck David Duke! The motherfucker [inaudible].

Axl would also talk about David Duke in interviews, like in an interview he did in September 1992:

When I read that Guns N' Roses could be David Duke's house band, that's wrong, and it hurts me. I'm not for David Duke. I don't know anything about the guy except that he was in the Klan, and that's f?!ked.

Last edited by Soulmonster on Sun Sep 11, 2022 6:34 pm; edited 16 times in total

Soulmonster- Band Lawyer

-

Posts : 15854

Plectra : 76906

Reputation : 831

Join date : 2010-07-06

Re: One In A Million

Re: One In A Million

Looking back at the song:

That's a song that the whole band says: 'Don't put that on there. You're white, you've got red hair, don't use it.' You know? 'Fuck you! I'm gonna do it cos I'm Axl!' OK, go ahead, it's your fucking head. Of course, you're guilty by association. [But] what are you gonna do? He's out of control and I'm just the fucking guitar player...

Axl's lyrics in 'One In A Million' immediately caught attention. The press labelled us things like David Duke's house band; I heard that the KKK - or some faction of the Klan at least - started using the song as a war cry. I stood by my original interpretation of the song and of Axl's intentions. Art gets misunderstood all the time. Still, I found myself uncomfortable as a result of this particular misunderstanding.

Duff's autobiography, "It's So Easy", 2011, p. 145

When I first heard 'One In A Million', I asked Axl, 'What the fuck? Is this necessary?' He just said, 'Yeah, it's necessary. I'm letting my feelings out.'

The Days of Wine and Roses, Classic Rock, April 2005

That song was meant, to the best of my knowledge, as a third-person slant on how fucked-up America was in the '80s. I don't know. I wouldn't have used the words, but Axl has been known to be amazingly bold at times.

Reverb, July 2010

'One In A Million' featured the wildly controversial lyrics about "police and niggers" and "immigrants and faggots." I thought that it was a great song that needed strong words. It expressed a heavy sentiment that had to be delivered with no punches pulled. I knew that the words weren't directed to the majority of blacks, gays, or immigrants. It simply described the scumbags of the world. (...) The song explained the shit that Axl, a naive hick from Indiana, had gone through.

"My Appetite for Destruction", 2010, pp. 177

I come from a family that’s multi-racial, Slash is half-black, and “One In A Million,” from where I sat in 1988—and I was convinced of it and still am, and people look at me cross-eyed—to me it was a commentary on America from a third person, and I thought it was the most genius thing ever, and I thought it was pretty bold of Axl to take that stance. We weren’t the huge band we’d become when Lies came out, but people knew who we were, so we knew people were gonna hear this song, but it wasn’t done for the shock value. It was kind of just recorded and done and out, and we were moving on. David Geffen had us on this AIDS benefit in 1989 or ’90, and it was gonna be at Radio City Music Hall, and we were the headliner for this thing. And the Gay Alliance or Rainbow Coalition or something gave David Geffen so much grief that we were kicked off. And it was really like, “Are you fuckin’ serious?” And that’s when it first started to dawn. I remember taking a flight home to Seattle and there was an empty seat next to me, and the flight attendant sat down, and she was a black woman. She said, “So, are you in the band Guns N’ Roses?” “Yeah.” “Are you really a racist?” She wanted to sit down and talk to me and try and turn me from being a racist. She was a nice Seattle chick, and I was a nice Seattle guy, and I just shrank in my seat. I didn’t know what to say.

[The Onion A.V. Club, May 2011

You know what, in all honesty [the problems with Living Colour] stemmed from a lyric that Axl, being from the Midwest in the US, from Indiana, he said something I didn't agree with when we recorded the song, he said something about niggers and faggots and something like that and it was his introduction to Los Angeles downtown. And I know where he's coming from in some ways, but I also know where he's really coming from in another way - and it wasn't necessary to say it, because you would really have to know his background to understand where that's coming from. It generated a lot of bad blood. I mean, I got jumped in Chicago because of it. By a bunch of my brothers, you know - about three of them - and they cornered me in a mall, in the dark, and I was like - "Look -" and I told them the same thing I'm telling you, look, you got to understand the guy, and we parted on good terms, but I understood why he shouldn't have done it in the first place. […] I said, well, if you insist on doing this, it's your responsibility, but in the long run it turns out to be the band's responsibility. In essence, we didn't ever have a problem with Living Colour as far as I know.

It hit home with me on a bad level, because I’m half black for one, so when we started saying the word [bleep], it got me very unsettling (laughs).

I was offended. That was a brash, ignorant kind of statement Axl made. I knew where he was coming from, once he explained it, but that didn't validate it to make it worthy of putting on a record.

We had issues. But the more issues we had, the more adamant he was about putting the song on there. I was hugely embarrassed that it was on something that my name was on. It was a tough little period.

We had issues. But the more issues we had, the more adamant he was about putting the song on there. I was hugely embarrassed that it was on something that my name was on. It was a tough little period.

[...] and a song Axl brought in lyrics for called 'One In A Million.' when he first showed them to us, I cringed at some of the words - especially 'niggers.' It wasn't that I thought Axl held racist views - there was never any question on that front. I realized Axl's lyrics represented a third-person observation about what Reagen-era America had become: a nation of name-callers, a land of fear. It was just a word my mouth would not form. Among my earliest memories as a child was my mom pulling me out of kindergarten to march in a peace rally after Martin Luther King was shot and killed. But Axl was bold. And nobody at the label seemed concerned

Duff's autobiography, "It's So Easy", 2011, p. 131

Last edited by Soulmonster on Wed Feb 16, 2022 8:10 am; edited 2 times in total

Soulmonster- Band Lawyer

-

Posts : 15854

Plectra : 76906

Reputation : 831

Join date : 2010-07-06

Re: One In A Million

Re: One In A Million

It's been confirmed it was played on the show in 1988. First post is updated.

Soulmonster- Band Lawyer

-

Posts : 15854

Plectra : 76906

Reputation : 831

Join date : 2010-07-06

Re: One In A Million

Re: One In A Million

From Los Angeles Times, October 15, 1989:

Behind the Guns N' Roses Racism Furor : The continuing debate over whether the band's song, 'One in a Million,' promotes bigotry

October 15, 1989|PATRICK GOLDSTEIN

Rock 'n' roll is in the hot seat again.

Call it media hype or justifiable outrage, but an acrimonious debate is raging over whether hard-rock heavyweights Guns N' Roses--as well as rap idols Public Enemy and speed-metal kings Slayer--are promoting bigotry and hatred.

Guns N' Roses has been under fire for a host of inflammatory lyrics in its song "One in a Million," which uses derogatory epithets to describe blacks and gays. The furor has continued, largely fueled by a Rolling Stone cover story in August. In that article, Guns N' Roses leader Axl Rose deepened the debate by stating: "Why can black people go up to each other and (use racial epithets), but when a white guy does it, all of a sudden it's a big put-down?"

Since then, rock and racism has become a hot story, with Guns N' Roses smack in the bull's-eye:

* A host of media outlets, from the "Today" show to the New York Times, have spotlighted heated reactions to the group's allegedly racist and anti-homosexual lyrics.

* Interviewing Boy George on his talk show, host Arsenio Hall blasted Rose as an "ignorant racist."

* In a letter to the New York Times, actor Sean Penn admiringly defended "One in a Million," comparing it to a Robert Capa war photo, labeling criticism of the band "pseudo-liberal hogwash."

* Parents Music Resource Center founder Tipper Gore also joined the debate, criticizing Guns N' Roses on "Entertainment Tonight" and, in a letter to the New York Times last Sunday, sounding the call for more "concern" and "outrage" about "troubling messages marketed to children through popular music."

In a full-page ad in Hollywood trade papers late last month, the Simon Wiesenthal Center asked the music industry: "Have we, as a nation, grown so apathetic about the racial, religious and sexual bias that is beginning to permeate our society? . . . Isn't it about time (the music industry) takes a firm stand against the immoral spread of hatred and bigotry?"

It's hard to believe that the Rolling Stones outraged parents and TV programmers two decades ago by singing "Let's Spend the Night Together." But now the Shock Rock mantle has been passed to Guns N' Roses, whose "One in a Million" offers a far more graphic--and vulgar--sketch of modern life. The song portrays a small-town boy's first fearful glimpse of grimy, downtown Los Angeles and uses scabrous, streetwise language--unsuitable for publication in this newspaper--replete with slurs against blacks, gays and immigrants.

The rock ballad attracted some initial media scrutiny when it was released late last year. But it didn't emerge as a cause celebre until a commentary published in the Village Voice in late August took the press to task for criticizing Public Enemy for anti-Semitic remarks by one of its members without expressing similar outrage over Rose's lyrics.

(Earlier this year, Prof. Griff, known as Public Enemy's Minister of Information, gave a much-publicized interview claiming that Jews were behind "a majority of wickedness that goes on across the globe." Though the group fired Griff, he was eventually reinstated, even though he refused to retract his remarks; in his most recent interview, he called his statements "100% pure.")

Defending his song in Rolling Stone, Axl Rose said he used a racial epithet because "it's a word to describe somebody that is basically a pain in your life, a problem. There's a rap group, N.W.A. . . . I mean, they're proud of that word. . . . I've had some very bad experiences with homosexuals. (But am I) anti-homosexual? I'm not against them doing what they do as long as they're not forcing it upon me."

Rose would not comment further, but his management firm issued a statement saying: "Guns N' Roses do not base their career on bigotry. . . . It is an artist's right to comment with honesty on both the beautiful and the ugly."

Are such racial epithets fair game because blacks use them too? Not at all, says Arsenio Hall.

"I never do--ever. And Guns N' Roses' attitude points out the very danger in using it. Because ignorant white people like Axl Rose are going to get the idea that's it's OK to use it too. The difference is very clear. N.W.A uses it in a figurative way, whereas Guns N' Roses uses it in a negative, derogatory way--as a white slavemaster would use it.

"There are rules of the turf. . . . I met several members of Guns N' Roses during the MTV Awards, and they seemed nice and decent. But Axl never said a word to me. And if we ever talk, I'll tell him another rule of the street. If you use that kind of language, you get your (rear-end) whipped. And I hope someone whips his (rear end) so he knows it's a mistake."

One thing is obvious--the debate over ethnic slurs has touched a raw nerve.

Soulmonster- Band Lawyer

-

Posts : 15854

Plectra : 76906

Reputation : 831

Join date : 2010-07-06

Re: One In A Million

Re: One In A Million

Article by John Pareles in The New York Times, September 10, 1989:

https://www.nytimes.com/1989/09/10/arts/pop-view-there-s-a-new-sound-in-pop-music-bigotry.htmlJohn Pareles wrote:POP VIEW; There's a New Sound in Pop Music: Bigotry

Has hatred become hip? From isolated spots in pop culture, racial and sexual prejudice have slithered back into view. Andrew Dice Clay, a comedian whose Nassau Coliseum performance on Saturday sold out immediately, mixes dirty-word jokes with vicious put-downs of women, homosexuals, blacks and Japanese. During a sketch on ''The Tonight Show'' Aug. 11, Johnny Carson, as his yokel character Floyd R. Turbo, invoked ''baseball the way it was meant to be played, on real grass, with no designated hitter and all white guys''; the studio audience gasped, then tittered nervously.

In a recent Rolling Stone magazine cover story, Axl Rose of the heavy metal band Guns N' Roses, whose debut album sold nine million copies, defends his song ''One in a Million,'' which includes the verse: ''Immigrants and faggots/ They make no sense to me/ They come to our country/ And think they'll do as they please/ Like start some mini-Iran or spread some [ expletive ] disease.'' He also savors the word ''niggers'' in a verse that continues, ''Get outta my way/ Don't need to buy none/ Of your gold chains today.''

Across the color line, the rap group Public Enemy fired, then rehired, Richard (Professor Griff) Griffin, who as its ''minister of information'' said in a May interview with The Washington Times: ''The Jews are wicked. And we can prove this.'' He went on to say that Jews are responsible for ''the majority of wickedness that goes on across the globe.'' Mr. Griffin was made the group's liaison to the black community and local youth programs, but no longer gives interviews. In a statement announcing the rehiring, Public Enemy's leader, Carlton (Chuck D.) Ridenhour, said, ''Please direct any further questions to Axl Rose.''

Meanwhile, numerous rappers include homophobic asides in the course of an album. For example, Heavy D. and the Boyz, whose album ''Big Tyme'' recently reached No. 1 on Billboard's black-music chart, boast that with their rhymes, ''you'll be happy as a faggot in jail.''

It's ugly stuff, and, as the sticker on Mr. Clay's album package puts it, ''offensive.'' While those examples are vastly outnumbered by non-racist, non-homophobic cultural messages, they are like cockroaches in a clean kitchen, signaling more trouble to come.