2003.03.DD - Modern Drummer - Josh Freese: In Demand

2 posters

Page 1 of 1

2003.03.DD - Modern Drummer - Josh Freese: In Demand

2003.03.DD - Modern Drummer - Josh Freese: In Demand

url=https://servimg.com/view/20053300/1959]

[/url]

[/url]

Transcript:

----------------------

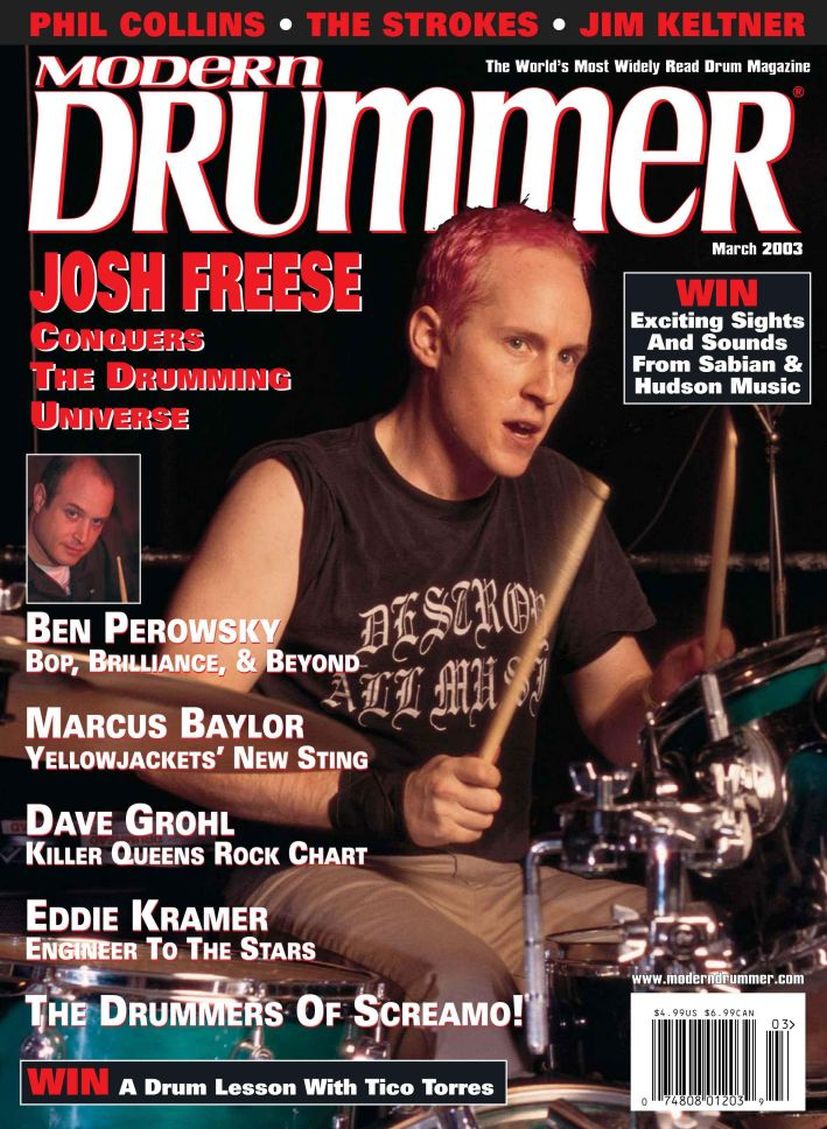

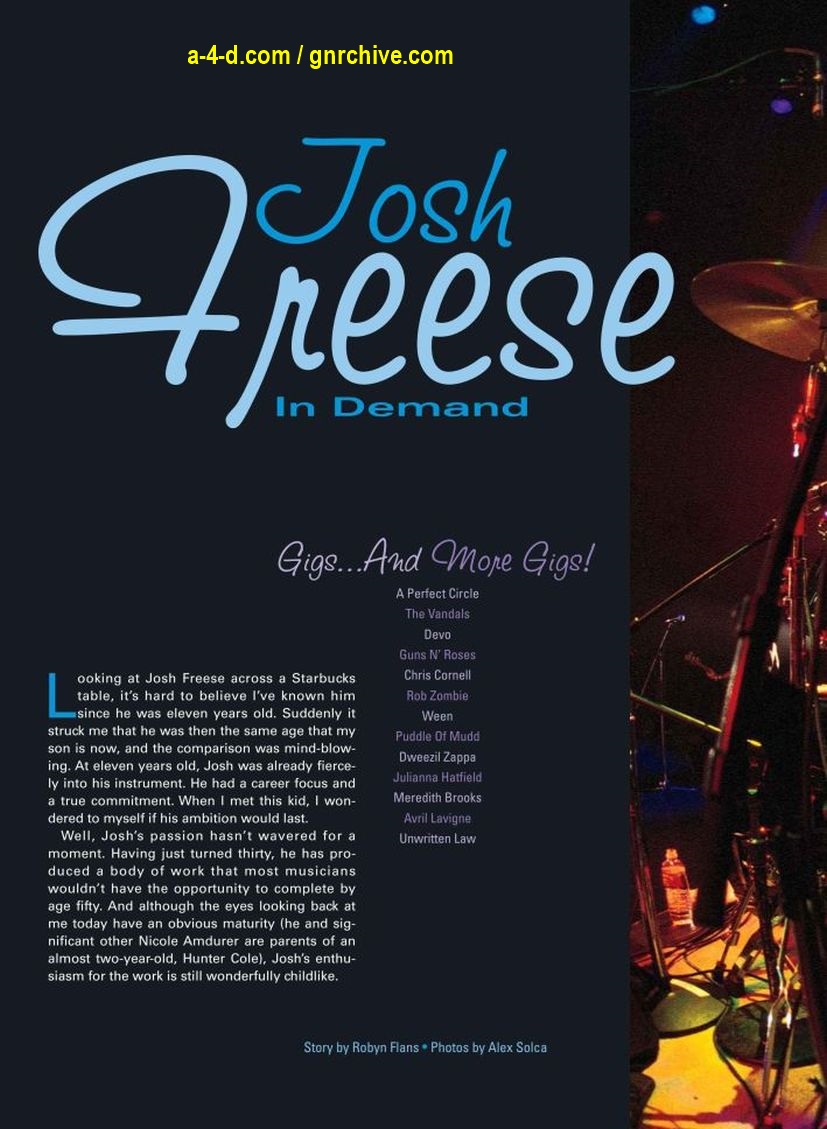

Josh Freese

In Demand

Gigs... And More Gigs!

A Perfect Circle

The Vandals

Devo

Guns N' Roses

Chris Cornell

Rob Zombie

Ween

Puddle Of Mudd

Dweezil Zappa

Julianna Hatfield

Meredith Brooks

Avril Lavigne

Unwritten Law

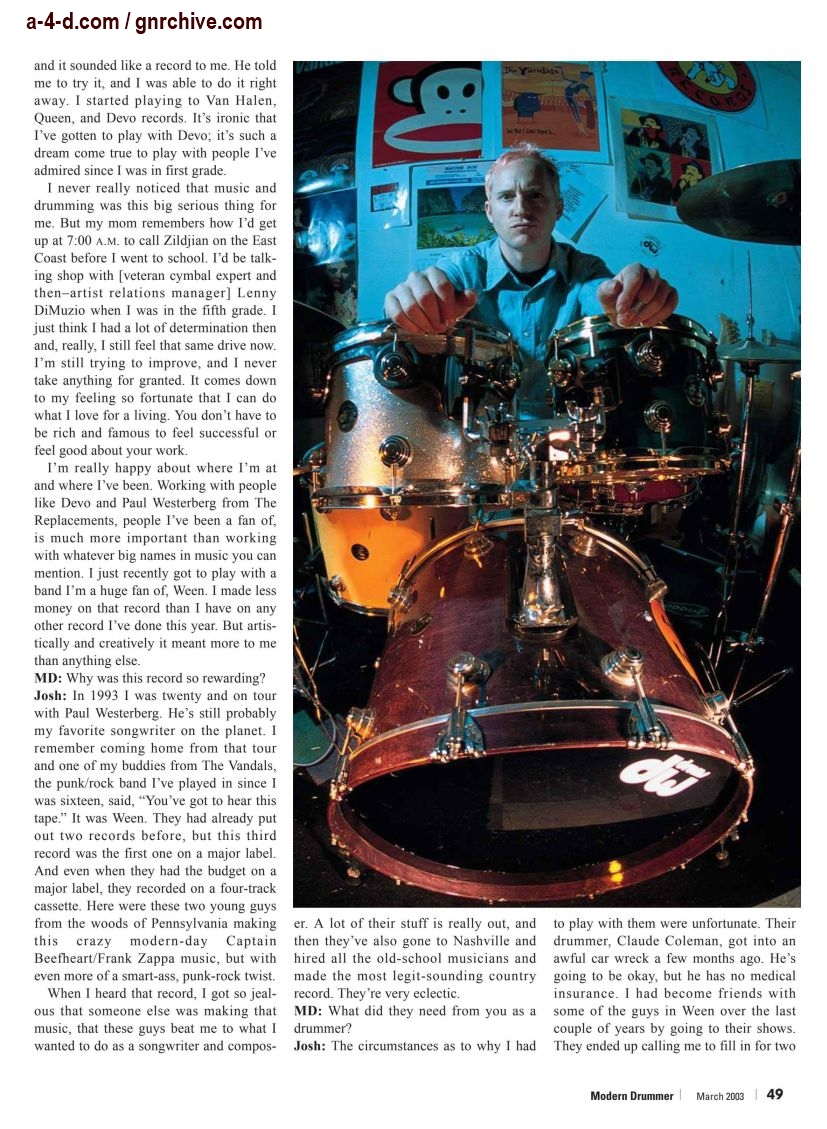

Story by Robyn Flans • Photos by Alex Solca

Looking at Josh Freese across a Starbucks table, it's hard to believe I've known him since he was eleven years old. Suddenly it struck me that he was then the same age that my son is now, and the comparison was mind-blowing. At eleven years old, Josh was already fiercely into his instrument. He had a career focus and a true commitment. When I met this kid, I wondered to myself if his ambition would last.

Well, Josh's passion hasn't wavered for a moment. Having just turned thirty, he has produced a body of work that most musicians wouldn't have the opportunity to complete by age fifty. And although the eyes looking back at me today have an obvious maturity (he and significant other Nicole Amdurer are parents of an almost two-year-old, Hunter Cole), Josh's enthusiasm for the work is still wonderfully childlike.

Freese took the instrument seriously from the get-go. His first drum teacher was Ron Romano, with whom he started when he was eight. Unfortunately that relationship ended when Josh’s dad, the director for the band at Disneyland in California, got Ron a job playing down at Disney World in Florida. “I cried when Ron left,” Josh admits. But watching his dad direct the Disneyland band, combined with playing to Devo records in his bedroom, seemed to be a productive next step for Freese, whose other significant teacher was Roy Burns. “He was a great teacher,” Josh says. “I’ve tried to teach, and I suck at it. People ask me all the time to give them lessons, and I tell them not to waste their time. Some guys are great teachers and some guys aren’t.” Josh has also taken lessons with drum giants like Terry Bozzio and Gregg Bissonette.

Another “tutor” for young Josh was Vinnie Colaiuta. The two met at a NAMM show when Josh was eleven, and it turned out to be an invaluable experience for the youngster, as Vinnie began regularly inviting him and his father down to LA club the Baked Potato to see the master play. “I’d sit behind Vinnie,” Josh says, “and I’d leave being half-inspired and half-discouraged. He was phenomenal, and then he’d be cool enough the next day when I’d call him at 9:00 a.m. to answer my stupid questions, like, ‘What kind of bass drum beater were you using last night?’ He had probably gotten to bed two hours before, but he was always cool to me.”

At that same NAMM show, Josh’s life took a major turn, when, while banging away on some Simmons electronic kits, the company took notice of his impressive playing and asked him to represent their company to the youth market. Simmons sent Freese to various NAMM shows to demonstrate the product, and even put him in a commercial. The only drawback for Josh was that he became tagged as “an electronic drummer,” and he spent the next three years as the electronic drummer beside the set drummer in a Disneyland band called Polo.

By age fifteen, Freese was itching to have some different experiences. “I grew up a huge Devo fan,” he admits, “but by the time I was eleven or twelve, I had read many articles in Modern Drummer with Terry Bozzio, Vinnie Colaiuta, and Chad Wackerman, where they were saying, ‘Playing with Frank Zappa was so challenging... playing with Frank was so this... playing with Frank was so that....’ So I started going out and buying Zappa records, and I became infatuated with that music at a pretty young and impressionable age.”

A chance meeting with Frank Zappa’s son Ahmet brought Freese to Ahmet’s brother Dweezil’s attention. Although he never played with Frank, Josh did have the thrill of watching him in the studio, and he did get to play with Dweezil. It was in Dweezil’s trio that Josh came in contact with one of his greatest mentors, Frank Zappa bassist Scott Tunis, who turned the youngster on to punk rock.

Aside from opening musical doors, Tunis, who was already an adult, taught Freese an even greater lesson about maintaining an open mind.

When Dweezil took a break, Freese landed his first major tour with Michael Damian, and eventually came in contact with the bands Infectious Grooves and Suicidal Tendencies. Before he knew it, Josh was getting an abundance of session calls for his ability in the studio to play spot-on but a little left of center. In the early ’90s, he hooked up with the punk band The Vandals and recorded and gigged with Paul Westerberg. Albums by Juliana Hatfield, Meredith Brooks, Chris Cornell, Tracy Bonham, Indigo Girls, and Puddle Of Mudd followed. Before he knew it, Josh was surprised to find himself voted number-2 studio drummer in the Modem Drummer Readers Poll.

Freese has never stopped long enough to realize that he is, in fact, a top studio musician, or fully acknowledge the recognition his position has brought him. Heck, Josh wasn’t even aware that he had recorded half of the recent multi-millionselling album by Avril Lavigne until way after its release. At that time, it had been just another session with a producer he knows. Listeners can be forgiven for not knowing all of Josh’s big credits, too, for instance, his uncredited appearance on Puddle Of Mudd’s huge Come Clean album. Sometimes the project name changes by the time the music is on the radio, so Freese is always amused when he finds out that he’s the drummer on the song he’s hearing on the radio.

According to Freese, many times the scenario goes like this: “I’ll get a call from a producer who says, ‘Josh, I need you in the studio next week. The band is back wherever they live. We have all the Pro Tools files open—it will be you, me, the computer, and an engineer. You have to redo three or four songs.’ So I’ll go in, knock out the tunes, and a lot of times I don’t even hear the finished record. Sometimes it ends up being a hit without my even realizing it.”

After being a member of Guns N’ Roses between 1998 and 2000, Josh left in favor of the varied menu of music to which he had become accustomed. He continues to play on and off with The Vandals and Paul Westerberg, while consistently getting involved with new projects that turn him on, such as A Perfect Circle, whose debut album, Mer De Noms, garnered critical acclaim right out of the gate, and an offshoot called Tapeworm.

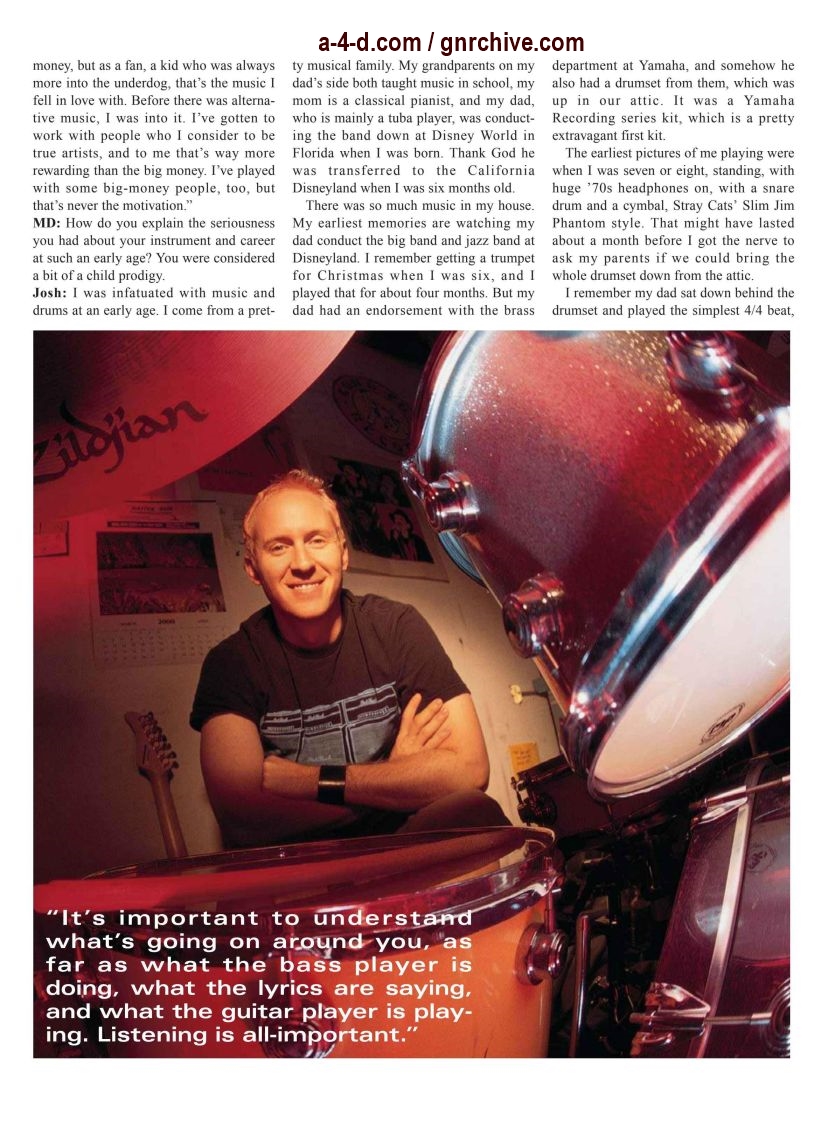

“I’ve tracked down, become friends with, and gotten to work alongside almost every one of my heroes,” Josh says. “A lot of those people don’t make a ton of money, but as a fan, a kid who was always more into the underdog, that’s the music I fell in love with. Before there was alternative music, I was into it. I’ve gotten to work with people who I consider to be true artists, and to me that’s way more rewarding than the big money. I’ve played with some big-money people, too, but that’s never the motivation.”

MD: How do you explain the seriousness you had about your instrument and career at such an early age? You were considered a bit of a child prodigy.

Josh: I was infatuated with music and drums at an early age. I come from a pretty musical family. My grandparents on my dad’s side both taught music in school, my mom is a classical pianist, and my dad, who is mainly a tuba player, was conducting the band down at Disney World in Florida when I was born. Thank God he was transferred to the California Disneyland when I was six months old.

There was so much music in my house. My earliest memories are watching my dad conduct the big band and jazz band at Disneyland. I remember getting a trumpet for Christmas when I was six, and I played that for about four months. But my dad had an endorsement with the brassdepartment at Yamaha, and somehow he also had a drumset from them, which was up in our attic. It was a Yamaha Recording series kit, which is a pretty extravagant first kit.

The earliest pictures of me playing were when I was seven or eight, standing, with huge ’70s headphones on, with a snare drum and a cymbal, Stray Cats’ Slim Jim Phantom style. That might have lasted about a month before I got the nerve to ask my parents if we could bring the whole drumset down from the attic.

I remember my dad sat down behind the drumset and played the simplest 4/4 beat, and it sounded like a record to me. He told me to try it, and I was able to do it right away. I started playing to Van Halen, Queen, and Devo records. It’s ironic that I’ve gotten to play with Devo; it’s such a dream come true to play with people I’ve admired since I was in first grade.

I never really noticed that music and drumming was this big serious thing for me. But my mom remembers how I’d get up at 7:00 a.m. to call Zildjian on the East Coast before I went to school. I’d be talking shop with [veteran cymbal expert and then-artist relations manager] Lenny DiMuzio when I was in the fifth grade. I just think I had a lot of determination then and, really, I still feel that same drive now. I’m still trying to improve, and I never take anything for granted. It comes down to my feeling so fortunate that I can do what I love for a living. You don’t have to be rich and famous to feel successful or feel good about your work.

I’m really happy about where I’m at and where I’ve been. Working with people like Devo and Paul Westerberg from The Replacements, people I’ve been a fan of, is much more important than working with whatever big names in music you can mention. I just recently got to play with a band I’m a huge fan of, Ween. I made less money on that record than I have on any other record I’ve done this year. But artistically and creatively it meant more to me than anything else.

MD: Why was this record so rewarding?

Josh: In 1993 I was twenty and on tour with Paul Westerberg. He’s still probably my favorite songwriter on the planet. I remember coming home from that tour and one of my buddies from The Vandals, the punk/rock band I’ve played in since I was sixteen, said, “You’ve got to hear this tape.” It was Ween. They had already put out two records before, but this third record was the first one on a major label. And even when they had the budget on a major label, they recorded on a four-track cassette. Here were these two young guys from the woods of Pennsylvania making this crazy modern-day Captain Beefheart/Frank Zappa music, but with even more of a smart-ass, punk-rock twist.

When I heard that record, I got so jealous that someone else was making that music, that these guys beat me to what I wanted to do as a songwriter and composer. A lot of their stuff is really out, and then they’ve also gone to Nashville and hired all the old-school musicians and made the most legit-sounding country record. They’re very eclectic.

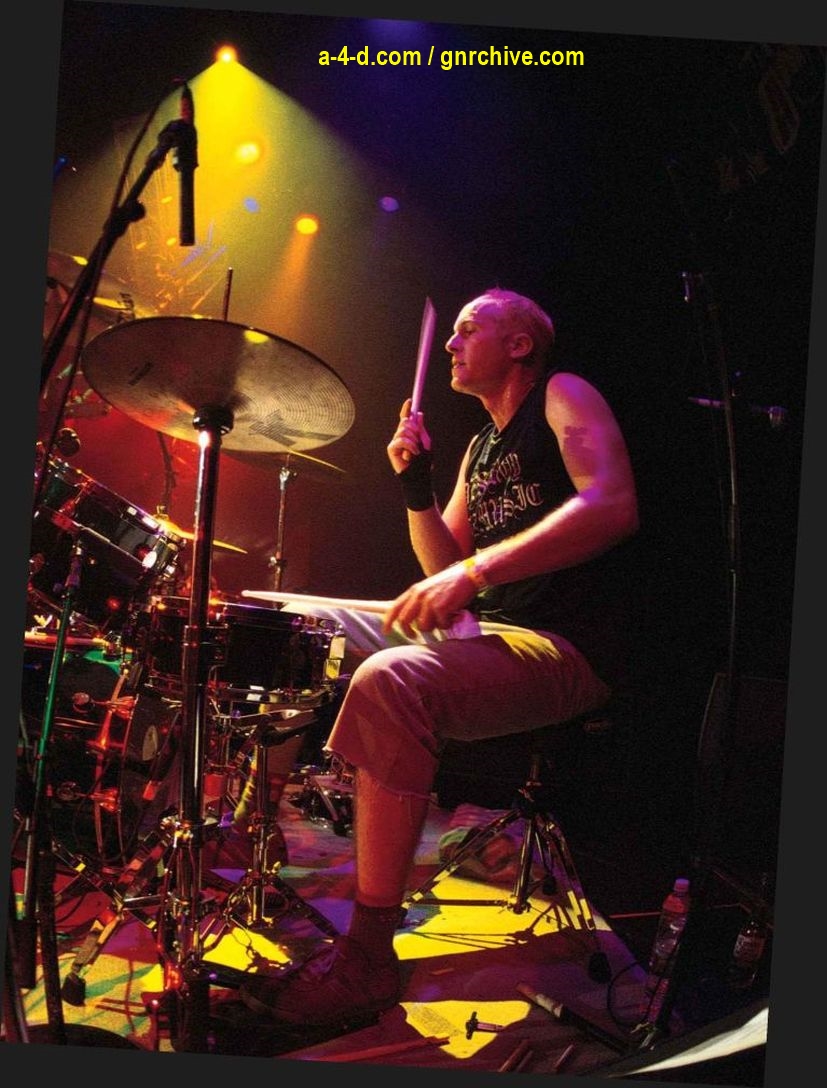

MD: What did they need from you as a drummer?

Josh: The circumstances as to why I had to play with them were unfortunate. Their drummer, Claude Coleman, got into an awful car wreck a few months ago. He’s going to be okay, but he has no medical insurance. I had become friends with some of the guys in Ween over the last couple of years by going to their shows. They ended up calling me to fill in for two shows at the Bowery Ballroom in New York, which were sold out, with the proceeds going to Claude.

I had a blast playing with Ween. They play forty songs a night that are completely mixed—one song is a legit-sounding country/Waylon Jennings-type tune, the next is a mock speed metal song, then Dixieland, Zeppelin, reggae, and even Captain Beefheart. The styles are all over the place, and the guys are really out approach-wise and lyrically.

MD: Bassist Scott Tunis was the one who really got you started appreciating that music.

Josh: Scott started me on the road of appreciating simple, soulful music and taught me that it doesn’t have to be tricky—it doesn’t have to be a circus act—to have validity. He taught me about the beauty of The Ramones and how important they are to popular music. I was thinking, “Really? The Ramones? How could this guy who can sightread all this crazy music tell me how important Dee Dee Ramone is as a bass player?” To this day, I carry that thought with me.

I would rather see someone play a Ramones’ song spot-on, with heart and soul, than play some lick they learned out of a book, with all the chops in the world. Chops can be fantastic to watch, but they don’t make the whole world tap their foot, cry, or get excited. Chops can make your jaw drop and your eyes widen for a few seconds, but the feeling in the heart is different.

Scott taught me the importance of everyone from Midnight Oil and The Butthole Surfers to The Sex Pistols. I had automatically discredited them in my mind because I was listening to jazz and fusion. But going through phases is part of the fun of being a teenager. One day you decide, “That band sucks, this is where it’s at.” And the next you decide, “That’s not where it’s at, this is.” All the phases bring you finally to a point where you’re not afraid to admit that you really liked this particular Tom Petty record. At nineteen or twenty, I wouldn’t have told my punk-rock friends that. But Tom Petty, and people like Jim Keltner, Jeff Porcaro, Charlie Drayton, and Steve Jordan, are classic examples of how amazing playing can be without it being a circus act.

Scott Tunis taught me the beauty of a guy playing 4/4, laying it down to the point where nothing else matters. That’s when you shake your head half in disgust because it’s so good and half in awe because you can’t believe you’re getting excited about someone playing a simple midtempo 4/4. That’s not supposed to be hard, but to make it feel that way is hard.

An example of that happened to me recently in the studio. I often get called to play on a track or two of a band where I don’t get credited, or sometimes it might say “additional percussion by Josh Freese,” but I really played on the three singles on the record. Sometimes it’s a band without a drummer, or they’ve fired the drummer in the middle of the record. I’ve been in every situation—the drummer is there and he’s pissed off, or the drummer is there and he’s excited that I’m going to help out, or the drummer isn’t there and the rest of the band is trying to keep him away from the studio.... It’s always some sort of weird political thing, and it’s egos, friendships, and business.

I remember the first time I was replaced in the studio, about ten years ago, and it was done behind my back. I don’t feel bad about it now, because not only have I since replaced guys who I think are great, but at the time I was only twenty. I recorded a track, but the producer didn’t have a check for me and told me to stop back whenever I was in the neighborhood to pick it up. This was someone I worked with all the time. So I pulled up to the studio the next day and heard live drums through the wall and thought, “Oh, he must be producing a band.” I walked in and started chatting with the secretary and suddenly realized I recognized the song— it was the same one I had recorded. I didn’t say anything and didn’t make anyone feel uncomfortable. I left feeling kind of sad, with my ego bruised, but it was probably good for me. I probably thought I was hot stuff at the time, so it was good for me. Now I realize it doesn’t mean that you didn’t do a good job.

I called that producer a couple of days later and said I didn’t want to put him on the spot, but I wanted to know what I did wrong. He explained that the artist felt the drums were tuned way too floppy and he wanted something a little more pop with a higher-pitched snare, and a little lighter approach. I still felt awful, but right around that same time—within a week— there was an article in Modern Drummer called “Getting Replaced In The Studio” with stories from guys like Jeff Porcaro, Jim Keltner, Denny Fongheiser, and Kenny Aronoff, and it made me feel better.

But back to my recent experience: I showed up at a studio to do four songs for a band making their first record on a major label. In the parking lot, I saw the drum tech, who I hadn’t seen for a while, and asked him what the scene in the studio was. He said, “The funny thing is, the drummer is a really good drummer, but he just isn’t working out on these songs.” I don’t want to say the drummer’s name, but he was used to playing speed metal and he’s amazing, and they were recording midtempo, slow songs. When I heard the tracks, I understood the problem right away, and the drummer was really open-minded and cool about the whole thing.

MD: Can you explain what they needed on this particular project?

Josh: They needed more space and choices of discretional fills. They needed someone who could do the “less is more” thing, which this other guy wasn’t used to. He was always pushed to play as fast as he could with as many fills as possible.

I remember when I was younger going to a studio in Orange County and hearing that a legendary punk rock drummer from the Midwest had been there the night before, and they wanted him to play this simple groove and he couldn’t do it. When you’re a kid, you think, “Oh, that’s easy, the hard stuff is playing fast and tricky.” But it’s that space in between the snare drum and where it lands that makes it feel the way it does.

My dad went to see Willie Nelson recently and came back exclaiming, “You won’t believe what the drummer [Paul English] played—just a snare drum!” He stood there with a snare drum and a stand, playing brushes 80% of the time, playing the train feel, and on the ballads he took a stick and did a sidestick on beat 4. My dad said it grooved like crazy. That’s hard to do. It’s so exposed. Any discrepancy is obvious.

MD: It sounds like the moral of the story is that not everyone is perfect for every situation.

Josh: Exactly. It’s like the sushi chef at the restaurant I love, who makes the most mind-boggling Japanese food I’ve ever had, trying to make a kick-ass burrito. He might suck at it, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t the most incredible Japanese chef you’ve ever encountered.

MD: To what do you attribute your success as a studio player?

Josh: I think it’s a combination of being into a lot of different kinds of music and understanding a lot of different kinds of music, and being open to things. I still feel that I have a hunger and a fire inside of me. I’m not jaded. I mean, I’ve been touring since I was fifteen, so sometimes I roll my eyes about something. But I always catch myself. If I’m complaining about something, I’ll laugh and go, “Why am I complaining about the food backstage? Who cares? I’m in New York City tonight, playing music for a living.”

I think the fact that I still love playing music makes a difference. A lot of it, I think, has to do with the fact that I got less into the circus tricks and more into people like Keltner, Jordan, and Porcaro. I think what also was important for me was playing other instruments and songwriting. I’m just as inspired by songwriters as I am by drummers, which can’t help but come out in my drumming.

It’s important to draw inspiration from whatever you’re inspired by. And it’s important to understand what’s going on around you, as far as what the bass player is doing, what the lyrics are saying, and what the guitarist is playing. Listening is all-important—listening to music in the car, going out and hearing people play, and then when you’re in the studio, listening to what’s going on around you and being supportive of that, being a team player rather than a hot dog. Get into country music, punk rock music, everything—Willie Nelson, The Ramones, Elvis Costello, Tom Petty. It’s so important to be open.

To me, there aren’t enough hours in the day for me to do what I want to do. Sometimes I feel narrow-minded; I’m not into sports or other things. Music is my hobby, my livelihood, my love. And there’s a lot of stuff out there that I haven’t even tapped yet that I know I will one day, like second-line drumming, New Orleans music, authentic jazz, and bebop.

MD: What happened with the Guns N’ Roses gig?

Josh: When I got the call to go down and audition for Guns N’ Roses, I was at a rehearsal place in LA doing pre-production for a record, and I had a message on my machine from their manager and thought, “What?!” I called him back, and he asked me if I wanted to audition. But it seemed too big, like a bigger-than-life band. I had a lot of things going on at the time, so I said, “I don’t know, it seems very time-consuming. I’ve got to think about it. I don’t want to waste your time if it isn’t something I really want to do.” He was cool about that, but he was persistent. A couple of days later he said, “Just come down and meet with Axl and the guys.”

I went down and auditioned for them, sick as a dog—I had eaten some bad seafood in London right before that, gotten on a plane, and auditioned that night. I was vomiting all the way to the rehearsal. Axl was totally cool, though, and very open-minded about music. He said, “I heard you played with Devo. I really liked Devo—and when I liked Devo, you got beat up for liking Devo.” I thought, “This guy is really cool.” It became obvious that he really listens to music. He was talking about artists all over the map.

They invited me down a second time, and from the beginning Axl was so nice and we got along and had a good time. He was completely open. So I decided to join. But as we started working together, things began taking such a long time—way too long for my taste. I got impatient and started thinking I wanted to do something else.

In ’97, when I was playing with Devo on the Lollapalooza tour, I had met Maynard [James Keenan] from Tool, and we became friends. One of the guys who was working with Axl on Pro Tools was Billy Howerdel. One day Billy said to me, “My roommate says he knows you.” It turned out to be Maynard, and we started saying “hi” to each other through Billy. One day Maynard said, “Josh writes good music—heavy music meets The Cocteau Twins or The Cure. It’s pretty linear and experimental to a degree while still staying in a pop realm. You should check it out.” That was the beginning of A Perfect Circle.

Maynard was busy with Tool, Billy and I were busy with Guns N’ Roses, but Billy ended up leaving, and I really liked the music we were doing together. And Maynard found the time as well. We were working at a friend’s home studio on spec, doing drum tracks there. Billy had a Pro Tools rig at his house and would do the overdubs there, so we were making a record without having a deal or even a name for the band. It started as a weekend project, but before we knew it, we said, “We’ve got a record.”

I really thought what we had were just demos, but that may be half the reason the drum tracks turned out so great. There was no pressure in a big studio with a producer or an A&R person. We were just hanging out at our friend’s house, and we’d have a few hours to do it. I’d say, “I really want to redo those drums someday,” and Billy would say, “Oh no, I love the fact that there’s a big huge fill after the first line of the first verse, where it’s not supposed to be. It’s pretty cool. I want to leave it that way.”

Well, we got a record deal with Virgin and a great mixer to mix what we recorded mostly in Billy’s garage, our friend’s house, and Sound City, where we did some of the drums. We figured out a name for the band, and all of a sudden we were on tour with Nine Inch Nails, doing arenas, a month before the album was to come out. When the album did come out, “Judith” became a hit, and we were all wondering how it happened. It was amazing. We had the highest-charting album by a debuting band ever. Our record entered the charts at number 4, and we sold something like 180,000 copies in the first week.

So A Perfect Circle was really what was behind my leaving Guns N’ Roses. I had to get out and play. I had been in the studio for a couple of years, and to Axl’s credit, he knows what he wants to hear, and he doesn’t want to put out anything less than incredible. In March of 2000, when I left, I knew the record was still far away from coming out. And since I had the opportunity to do something with friends I liked and music I loved, I had to leave. And frankly, I’m really proud of A Perfect Circle.

After that record, we knew Maynard would have to go back to Tool, and they put out Lateralus and went on tour for about a year and a half, selling out everywhere. During that time Billy has built a great home studio, we’ve got a ton of tracks done, and Maynard sends us lyrics to the songs. We send stuff out to him and he’ll write to it, so he’s been working on it while he’s been on tour. Once again, we’re making a record without really knowing we’re making a record. We’re shooting for our album to come out in the next few months. Then we’ll go on the road this summer.

And as an offshoot of A Perfect Circle, Maynard and I did another project called Tapeworm, which is a collaboration between Maynard, me, and Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails. We went down to Southern Tracks in Atlanta to cut the drums, and now Trent is finishing everything at his studio in New Orleans.

MD: You’ve also been on tour with The Vandals recently supporting Internet Dating Superstuds. After so many years, the band still seems very important to you.

Josh: The Vandals are like home to me. I recently had an opportunity to join a new band for a ton of money—more money than I’ve ever made, times two. But I wasn’t in love with the material. To stop everything that I love doing and put my reputation on the line by saying, “This is what I’m about, 110%,” well, I couldn’t do it. A friend of mine said to me, “Even though you’re not making nearly that amount of money, you’re doing well doing exactly what you want to do. Why go make more money doing something you don’t want to do?” That was a great point.

The Vandals are like my social time, too. It’s a business and it’s music, but socially it’s really rewarding too. They are three of my closest friends on the planet. We go to Australia twice a year and Europe three times a year. We don’t sell millions of records, but it’s been an underground band that has toured the world, put out a bunch of records, and been successful on a decent level. As my dad recently put it, “The Vandals are so good for your head. Some guys play poker, some guys go fishing with their friends on the weekend, and you play in The Vandals.” That’s the truth.

Last edited by Blackstar on Thu Feb 04, 2021 2:08 pm; edited 1 time in total

Blackstar- ADMIN

- Posts : 13871

Plectra : 91040

Reputation : 101

Join date : 2018-03-17

Re: 2003.03.DD - Modern Drummer - Josh Freese: In Demand

Re: 2003.03.DD - Modern Drummer - Josh Freese: In Demand

Josh gives the best, most eloquent answers of them all. Great guy.

Soulmonster- Band Lawyer

-

Posts : 15958

Plectra : 77296

Reputation : 830

Join date : 2010-07-06

Similar topics

Similar topics» 2014.08.21 - Vice - Josh Freese of Devo and the Vandals Is the Blue Collar Freelance Drummer to the Stars

» 2020.08.24 - Drinks With Johnny Podcast - Interview with Josh Freese

» 2021.10.25 - Let There Be Talk - Interview with Josh Freese

» 1998.03.05 - MTV News - Axl Drummer Freese?

» 2000.03.14 - Allstarmag - Josh Freese Leaves Guns N' Roses

» 2020.08.24 - Drinks With Johnny Podcast - Interview with Josh Freese

» 2021.10.25 - Let There Be Talk - Interview with Josh Freese

» 1998.03.05 - MTV News - Axl Drummer Freese?

» 2000.03.14 - Allstarmag - Josh Freese Leaves Guns N' Roses

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum|

|

|