2019.05.08 - Kerrang! - Duff McKagan: Life, Loss & The Future of Guns N' Roses

Page 1 of 1

2019.05.08 - Kerrang! - Duff McKagan: Life, Loss & The Future of Guns N' Roses

2019.05.08 - Kerrang! - Duff McKagan: Life, Loss & The Future of Guns N' Roses

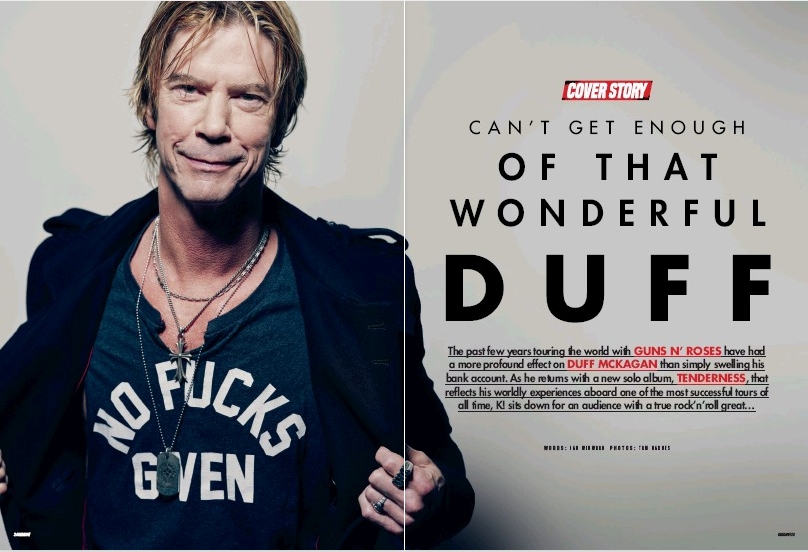

CAN’T GET ENOUGH

OF THAT WONDERFUL DUFF

The past few years touring the world with GUNS N’ ROSES have had a more profound effect on DUFF MCKAGAN than simply swelling his bank account. As he returns with a new solo album, TENDERNESS, that reflects his wordly experiences aboard one of the most successful tours of all time, K! sits down for an audience with a true rock ‘n’ roll great....

WORDS: IAN WINWOOD

PHOTOS: TOM BARNES

Duff McKagan is scrolling through his phone, searching for a joke. He is doing this is in response to an enquiry as to whether the device contains the number of one Axl Rose, his bandmate in Guns N’ Roses, or whether communications between the group’s members are facilitated by their individual managers. Our interviewee laughs at the notion that such barriers and walls still exist between men whose recent reconciliation with the Not In This Lifetime caravan ranks as the third highest-grossing tour in the history of music.

“Me and Axl text each other, like, every other day,” he says.

What kinds of things do you text?

“Jokes mostly.”

Right. Could you give us an example, please?

“Sure.”

And off he goes, thumbing through his phone. He finds a video that Axl sent yesterday, considers it for a moment, and then moves on. He skim-reads a couple of gags that aren’t deemed fit for purpose, before settling on one that is.

“Okay.”

Duff Mckagan clears his throat. “A six-foot beetle knocked on my door,” he says. “I opened it and it slapped me in the face. I guess there’s a nasty bug going around.”

Silence.

“They’re dad jokes, mostly.”

When ensconced in the press-proof ecosystem of Guns N’ Roses, Duff Mckagan doesn’t speak to journalists because, well, he doesn’t need to. “Guns”, as he sometimes calls them, announce a stadium tour, the tour sells out, and then the band hit the road. This they do with minimum fuss and maximum efficiency, news indeed to those who estimated that the Not In This Lifetime tour, now into its fourth year, would last about 25 minutes. Duff, Axl and Slash have separate dressing rooms and ride in their own tour buses – this is not unusual, by the way – but the reignition of a band that for decades was a byword for dysfunction meant that Guns N’ Roses are the authors of an unlikely happy ending at a time when many other artists of their vintage were succumbing to tragedy. Of this experience, Duff says that “the best thing about it, about getting back together, was getting in a room together and talking things through as grown men”.

He adds, “We took accountability and we talked through things in the past that had been problems. Everything in life happens for a reason. I had to go on a separate journey on my own. I can’t speak for Axl and Slash, but that’s definitely true for me. And my own journey has made me a better bandmate and friend and business partner, all of the things you have to be when you’re in a band. I’m now much better at those things. I’m much more capable now.”

It’s the last Saturday morning in April, and Duff Mckagan is in London to talk about his forthcoming album, Tenderness, his first solo outing for 20 years. Restrained and at times bracingly reflective, the 11-song set is the offering of a man who has clearly done some work on himself, and for whom, perhaps, life is no longer always quite so easy as it once was. Created in collaboration with the country singer-songwriter and producer Shooter Jennings, among others, Tenderness began life not as an album, but as a book (it would have been the New York Times bestselling author’s third). Harvested from a view of the world gained while travelling with Guns N’ Roses, it is a State of the Union address from a man who, by any measure, has lived a little.

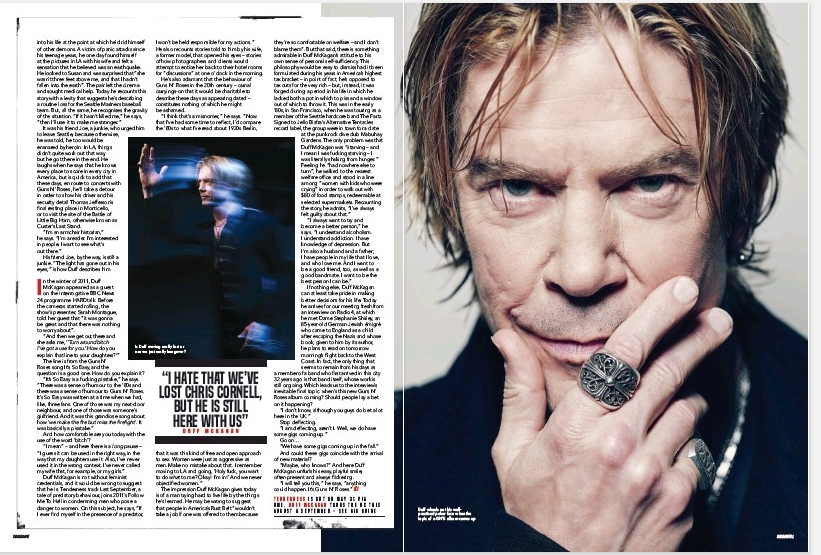

Despite years of sobriety, Duff Mckagan still looks the part. After all, who but a rock icon with impeccable bona fides could pull off a T-shirt that features the words ‘No Fucks Given’? At 55, he is as lithe as the Pink Panther, even if his speech betrays the drawling patterns of one who has put in some serious time fucking himself up. In conversation, it’s difficult for the interviewer not to fleetingly think of some of the things the American has seen, and done. In the 20th century, chaos abounded. A riot at a Guns N’ Roses show in St Louis in 1991 resulted in roughly $200,000 worth of damage at the then brand-new Riverport Performing Arts Center. Another scene at the Olympic Stadium in Montreal was quelled only after the intervention of 300 riot police officers. This unpleasantness in Canada occurred during the now infamous Monsters Of Rock tour of 1992, a co-headline caravan with Metallica at which Guns N’ Roses were said to be spending $100,000 a night on after-show parties. By this point, for Duff Mckagan things were getting out of hand, so much so that today he claims not to be able to remember anything from the year that followed. By 1994, his pancreas had swollen to the size of an American football, its subsequent bursting causing third-degree burns to his insides. He was told that if he didn’t stop drinking, he’d be dead in less than a month. Today, lunch consists of a salad.

“Funnily enough, it was while writing my first book [It’s So Easy & Other Lies: The Autobiography, from 2012] that I learned to be really fucking honest about what my life used to look like,” he says. “There were passages from that book that were just lies. I’d write 4,000 words of bullshit passages about how something went down, and it was always someone else’s fault. It was never my fault. I was lying to myself, and had I not deleted those passages, I would have been lying to the reader, too. But I looked at what I’d written and thought to myself, ‘You know that’s not how it fucking went down.’ I had to be a better fucking man than that. But I learned to be honest with myself, and to take responsibility for my part in fuck-ups. And that really gave me some clarity. I thought I’d really taken care of all that shit through getting sober, but it turned out that I had deeper still to dive.

“And I tell you, being accountable is not easy. It can be hard to say, ‘Oh, maybe the problem was actually me…’”

But talk about an impressive second act. It’s fitting that today’s interview takes place in one of the many shinily impressive new office blocks that have emerged over recent years in London’s King’s Cross, and which have erased the neighbourhood’s long-held reputation for hard drugs and reckless living. A man of energy, Duff Mckagan has likewise turned his focus from an appetite for destruction to achievements of which he is rightly proud. Today his life is a curriculum vitae of productivity. An alumnus of Seattle University, over the years he has also made his name as a magazine and website columnist, the founder of a wealth management firm, and an activist for ex-service personnel; as well as this, he is a husband and a father. His eldest daughter, Grace, performs in her own band, The Pink Slips, who practise in the basement of her parents’ home in Los Angeles, a space that was once utilised by The Dickies, one of the city’s finest original punk bands.

As well as this, he has also been a mentor to others. One of Tenderness’ standout tracks is Feel, a composition that its author claims “took three minutes to write”, a fact that is remarkable seeing as the song is more than four minutes long. The lyric tells the story of a man’s doomed attempt to walk into the light, but who, instead, “went back to drugs”. This is a specific reference to Scott Weiland, a friend and one-time bandmate in Velvet Revolver, who died of an accidental overdose in 2015.

“[Feel] was the result of me still wrestling with Scott’s death,” Duff says. “I’ve lost so many friends, but with this one I was struggling with survivor’s guilt, I guess you’d call it. Once he went back to drugs, the game was up. ‘You go back to drugs, you’re gonna die’ – I told him that. I said, ‘You know where this is gonna go, Scott.’ But he said, ‘No, no, man, I got this.’ And then he was gone. I’ve gotta be honest, I didn’t know where to place that in my life.”

The guilt seems unjustified. Following the wreckage from the initial implosion of Stone Temple Pilots, Duff Mckagan took personal charge of weaning Scott Weiland off heroin. Along with Dave Kushner, later of Velvet Revolver, and, improbably, a kung fu shifu, they took themselves off to the Cascade Range of mountains in Washington State and, over the course of a month, cleaned up their friend.

“Me and Scott had gone through so much,” he says. “I shot him in the ass to wean him off heroin. I personally did that – for a month. He got his family back; he had his victory. He came to me for help because he wanted to get sober the way I got sober. I was, like, ‘Okay, then we’re going. It’s gonna be tough, but we’ll get through it.’”

The Cascades overlook Seattle, a city the superior musical legacy of which is shrouded in death. Duff Mckagan gives short shrift to the notion that there is anything exceptional about his hometown – “It’s a port city,” he says, “there’s a lot of heroin, but there’s nothing more to it than that” – but, even so, he once shared a flight with Kurt Cobain in the week of the Nirvana frontman’s suicide, and, as a member of Mad Season, shared a stage with Chris Cornell, in Seattle, the year before he passed away. In the wake of this passing, a well-judged section of Guns N’ Roses’ reunion live set was the inclusion of a cover of Soundgarden’s Black Hole Sun.

Today, Duff says, “I knew the other Chris, the one I knew before [he became ill]. His then wife Susan [Silver] and my wife Susan were pregnant with our respective daughters, who were born two weeks apart [in 2000],” he says. “She’s a wonderful woman, and Lily, her daughter, is a wonderful girl. She’s the same age as my [youngest] daughter Mae. I knew Chris struggled with depression, and I hate that he’s gone. But that we’re talking about him means he’s still here with us.”

Duff Mckagan then tells a story about his own depression, a condition that came slam-dancing into his life at the point at which he’d rid himself of other demons. A victim of panic attacks since his teenage years, he one day found himself at the pictures in LA with his wife and felt a sensation that he believed was an earthquake. He looked to Susan and was surprised that “she wasn’t three feet above me, and that I hadn’t fallen into the earth”. The pair left the cinema and sought medical help. Today he recounts this story with a levity that suggests he’s describing a routine loss for the Seattle Mariners baseball team. But, all the same, he recognises the gravity of the situation. “If it hasn’t killed me,” he says, “then I’ll use it to make me stronger.”

It was his friend Joe, a junkie, who urged him to leave Seattle, because otherwise, he was told, he too would be ensnared by heroin. In LA, things didn’t quite work out that way, but he got there in the end. He laughs when he says that he knows every place to score in every city in America, but is quick to add that these days, en route to concerts with Guns N’ Roses, he’ll take a detour in order to show his driver and his security detail Thomas Jefferson’s final resting place in Monticello, or to visit the site of the Battle of Little Big Horn, otherwise known as Custer’s Last Stand.

“I’m an armchair historian,” he says. “I’m a reader. I’m interested in people. I want to see what’s out there.”

His friend Joe, by the way, is still a junkie. “The light has gone out in his eyes,” is how Duff describes him.

In the winter of 2011, Duff Mckagan appeared as a guest on the interrogative BBC News 24 programme HARDtalk. Before the cameras started rolling, the show’s presenter, Sarah Montague, told her guest that “it was gonna be great and that there was nothing to worry about”.

“And then we get out there and she asks me, “Turn around bitch I’ve got a use for you.’ How do you explain that line to your daughters?’”

The line is from the Guns N’ Roses song It’s So Easy, and the question is a good one. How do you explain it?

“It’s So Easy is a fucking pisstake,” he says. “There was a sense of humour to the ’80s and there was a sense of humour to Guns N’ Roses. It’s So Easy was written at a time when we had, like, three fans. One of those was my next-door neighbour, and one of those was someone’s girlfriend. And it was this grandiose song about how ‘we make the fire but miss the firefight’. It was basically a pisstake.”

And how comfortable are you today with the use of the word ‘bitch’?

“I mean” – and here there is a long pause – “I guess it can be used in the right way, in the way that my daughters use it. Also, I’ve never used it in the wrong context. I’ve never called my wife that, for example, or my girls.”

Duff Mckagan is not without feminist credentials, and it would be wrong to suggest that he is. Tenderness track Last September, a tale of predatory behaviour, joins 2011’s Follow Me To Hell in condemning men who pose a danger to women. On this subject, he says, “If I ever find myself in the presence of a predator, I won’t be held responsible for my actions.” He also recounts stories told to him by his wife, a former model, that opened his eyes – stories of how photographers and clients would attempt to entice her back to their hotel rooms for “discussions” at one o’clock in the morning.

He’s also adamant that the behaviour of Guns N’ Roses in the 20th century – carnal carryings-on that it would be charitable to describe these days as appearing dated – constitutes nothing of which he might be ashamed.

“I think that’s a misnomer,” he says. “Now that I’ve had some time to reflect, I’d compare the ‘80s to what I’ve read about 1920s Berlin, that it was this kind of free and open approach to sex. Women were just as aggressive as men. Make no mistake about that. I remember moving to LA and going, ‘Holy fuck, you want to do what to me? Okay! I’m in!’ And we never objectified women.”

The impression Duff Mckagan gives today is of a man trying hard to live life by the things he’s learned. He may be wrong to suggest that people in America’s Rust Belt “wouldn’t take a job if one was offered to them because they’re so comfortable on welfare – and I don’t blame them”. But that said, there is something admirable in Duff Mckagan’s attitude to his own sense of personal self-sufficiency. This philosophy would be easy to dismiss had it been formulated during his years in America’s highest tax bracket – in point of fact, he’s opposed to tax cuts for the very rich – but, instead, it was forged during a period in his life in which he lacked both a pot in which to piss and a window out of which to throw it. This was in the early ‘80s, in San Francisco, when he was touring as a member of the Seattle hardcore band The Fartz. Signed to Jello Biafra’s Alternative Tentacles record label, the group were in town for a date at the punk rock dive club Mabuhay Gardens. The only problem was that Duff Mckagan was “starving – and I mean I was fucking starving – I was literally shaking from hunger.” Feeling he “had nowhere else to turn”, he walked to the nearest welfare office and stood in a line among “women with kids who were crying” in order to walk out with $80 of food stamps, redeemable at selected supermarkets. Recounting the story, he admits, “I’ve always felt guilty about that.”

“I always want to try and become a better person,” he says. “I understand alcoholism. I understand addiction. I have knowledge of depression. But I’m also a husband and a father; I have people in my life that I love, and who love me. And I want to be a good friend, too, as well as a good bandmate. I want to be the best person I can be.”

If nothing else, Duff Mckagan can at least take pride in making better decisions for his life. Today he arrives for our meeting fresh from an interview on Radio 4, at which he met Dame Stephanie Shirley, an 85-year-old German-Jewish émigré who came to England as a child after escaping the Nazis and whose book, given to him by its author, he plans to read on tomorrow morning’s flight back to the West Coast. In fact, the only thing that seems to remain from his days as a member of a band who first arrived in this city 32 years ago is that band itself, whose work is still ongoing. Which leads us to the interview’s inevitable final topic: when’s this new Guns N’ Roses album coming? Should people lay a bet on it happening?

“I don’t know, although you guys do bet a lot here in the UK.”

Stop deflecting.

“I am deflecting, aren’t I. Well, we do have some gigs coming up.”

Go on…

“We have some gigs coming up in the fall.”

And could these gigs coincide with the arrival of new material?

“Maybe, who knows?” And here Duff Mckagan unfurls his easy, playful smile; often present and always flickering.

“I will tell you this,” he says, “anything could happen. It’s Guns N’ Roses.”

***

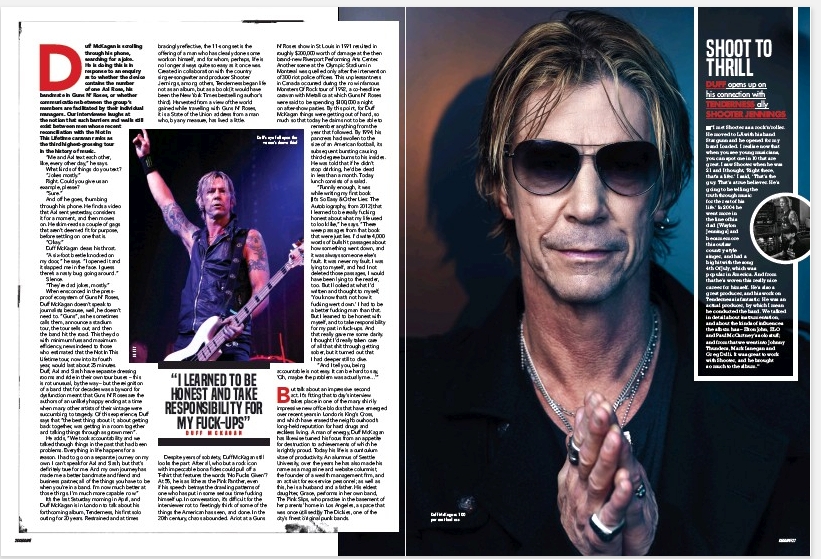

SHOOT TO THRILL

DUFF opens up on his connection with TENDERNESS ally SHOOTER JENNINGS

“I met Shooter as a rock’n’roller. He moved to LA with his band Stargunn and he opened for my band Loaded. I realise now that when you see young musicians, you can spot one in 10 that are great. I saw Shooter when he was 21 and I thought, ‘Right there, that’s a lifer.’ I said, ‘ That’s the guy. That’s a true believer. He’s going to be telling the truth through music for the rest of his life.’ In 2004 he went more in the line of his dad [Waylon Jennings] and became more this outlaw country-style singer, and had a big hit with the song 4th Of July, which was popular in America. And from that he’s woven this really nice career for himself. He’s also a great producer, and his work on Tenderness is fantastic. He was an actual producer, by which I mean he conducted the band. We talked in detail about instrumentation, and about the kinds of influences the album has – Elton John, ELO and Paul Mccartney’s solo stuff; and from that we went into Johnny Thunders, Mark Lanegan and Greg Dulli. It was great to work with Shooter, and he brought so much to the album.”

***

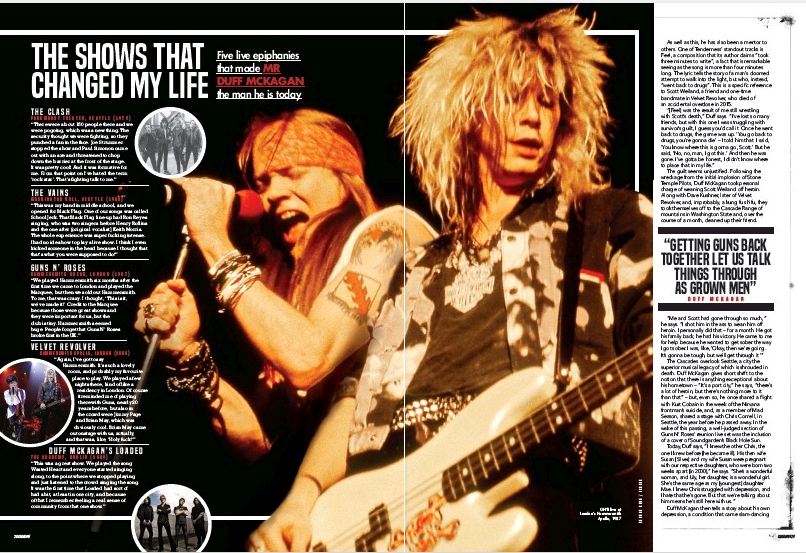

THE SHOWS THAT CHANGED MY LIFE

Five live epiphanies that made MR DUFF MCKAGAN the man he is today

THE CLASH

PARAMOUNT THEATER, SEATTLE (1979)

“There were about 150 people there and we were pogoing, which was a new thing. The security thought we were fighting, so they punched a fan in the face. Joe Strummer stopped the show and Paul Simonon came out with an axe and threatened to chop down the barrier at the front of the stage. It was pretty cool! And it was formative for me. From that point on I’ve hated the term ‘rock star’. That’s fighting talk to me.”

THE VAINS

WASHINGTON HALL, SEATTLE (1980)

“This was my band in middle school, and we opened for Black Flag. One of our songs was called School Jerk. That Black Flag line-up had Ron Reyes singing, who was two singers before Henry Rollins and the one after [original vocalist] Keith Morris. The whole experience was super fucking intense. I had no idea how to play a live show. I think I even kicked someone in the head because I thought that that’s what you were supposed to do!”

GUNS N’ ROSES

HAMMERSMITH ODEON, LONDON (1987)

“We played Hammersmith six months after the first time we came to London and played the Marquee, but then we sold out Hammersmith. To me, that was crazy. I thought, ‘ This is it, we’ve made it!’ Credit to the Marquee because those were great shows and they were important for us, but the club is tiny. Hammersmith seemed huge. People forget that Guns N’ Roses broke first in the UK.”

VELVET REVOLVER

HAMMERSMITH APOLLO, LONDON (2005)

“Again, I’ve got to say Hammersmith. It’s such a lovely room, and probably my favourite place to play. We played a few nights there, kind of like a residency in London. Of course it reminded me of playing there with Guns, nearly 20 years before, but also in the crowd were Jimmy Page and Brian May, which was obviously cool. Brian May came out onstage with us, actually, and that was, like, ‘Holy fuck!’ “

DUFF MCKAGAN’S LOADED

THE ACADEMY, DUBLIN (2009)

“This was a great show. We played the song Wasted Heart and everyone started singing along, to the point where we stopped playing and just listened to the crowd singing the song. It was the first time that Loaded had sort of had a hit, at least in one city, and because of that I remember feeling a real sense of community from that one show.”

https://www.pressreader.com/uk/kerrang-uk/20190508

Blackstar- ADMIN

- Posts : 13787

Plectra : 90377

Reputation : 101

Join date : 2018-03-17

Similar topics

Similar topics» 2019.05.28 - Metro - Guns N’ Roses’ Duff McKagan on social media and rebelling against ‘the man’

» 2019.03.20 - Forbes - Duff McKagan On His New Album, Guns 'N' Roses And The America He Believes In

» 2019.08.29 - Hot Press - Duff McKagan talks Guns N'Roses and hitting Stradbally

» 2019.06.13 - Entertainment Weekly - Duff McKagan on working with Shooter Jennings and new Guns N' Roses music

» 2019.06.24 - Spotify For the Record - Guns N’ Roses Bassist Duff McKagan Sings a Message of Hope

» 2019.03.20 - Forbes - Duff McKagan On His New Album, Guns 'N' Roses And The America He Believes In

» 2019.08.29 - Hot Press - Duff McKagan talks Guns N'Roses and hitting Stradbally

» 2019.06.13 - Entertainment Weekly - Duff McKagan on working with Shooter Jennings and new Guns N' Roses music

» 2019.06.24 - Spotify For the Record - Guns N’ Roses Bassist Duff McKagan Sings a Message of Hope

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum